This is partly inspired by the Op Ed that was in the Washington Post a few days back. It was a so-so article, there were some things that I felt weren’t fully explored, but then on the other hand it was just a brief article for an audience with no background in the Indian film industry, so he couldn’t really explore everything. But I can! I want to zero in on one point from the article, how there are so few films with women working behind the scenes, and even fewer films with real female lead roles. This isn’t something that just came up in the past year, and it isn’t something that will be solved overnight.

Non-Usual Disclaimer: I have no special knowledge of anything, this is all from public records, interviews, things I have heard third hand at parties, and various reprinted primary source materials in academic texts. But if I put it altogether, here is the simple straight-forward picture as it appears to me.

There’s a term I learned from the book version of Guide, “Public woman”. I am sure it is something that Narayan was translating from Tamil into English, but even in English the meaning is pretty clear. It means a woman who interacts with and is visible to the public.

This could be anything from someone who works behind the counter at a department store to a streetwalker. They are all lumped in under the same category of “public woman”. Whereas a non-public woman would be someone who goes from her father’s house to her husband’s house, and only steps outside those doors when accompanied by a close family member, a father-in-law, a brother-in-law, a husband, or an elderly mother-in-law.

(Notice how Rani tends to be seen with Uday or Pam Aunty most of the time she is in public now)

I’m giving you the broad framework, because you have to start with this huge general statement that affects all areas of female life, before you can even start talking about film. In the same way that you can’t really talk about Hollywood’s gender issues until you fully understand micro-aggressions and issues with career-path streaming in film schools and all of that stuff. It doesn’t start the day a studio head is looking at a list of directors and picking the male name, it comes much earlier than that.

When I was in India the first time, what was the biggest culture shock for me was to walk around the downtown area of Bombay and see no women on the street. And then, almost as much of a shock, we got lost and ended up wandering through some back alley areas, and suddenly there were only women! Women and children. There is a massive obvious gender divide that runs through all of society, the assumption is that the vast majority of people working outside of homes will be men, and the vast majority of people working out of homes will be women. And that’s the starting point when we talk about the gender divide in Indian film, before a little girl even wants to be a filmmaker, she has to want to and fight for the right to leave the home.

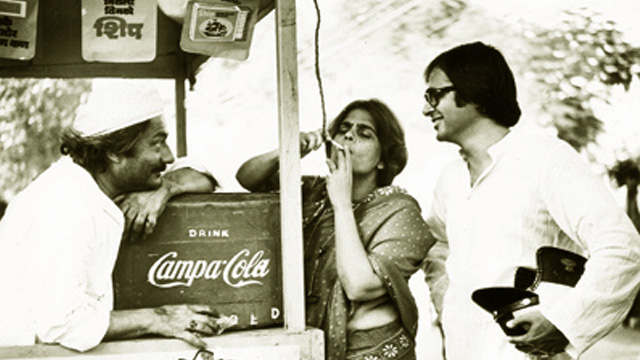

(see? All men!)

As the decades have passed in India, more and more professions have been labeled as “female”. Doctors, teachers, interior decorators, social workers, flight attendants. It starts as a perception problem, they had to be promoted as female professions, not male (and film was part of this, modeling working women in these positions) so that society would see them as “Respectable” for women. But there were also some basic safety considerations that had to be in place. Hostels, for one thing. Hospitals, schools, and airlines all provide housing for their female employees. And usually shuttles to and from work (if you aren’t working in the same place you live). Hostels usually have chaperons and curfews and all sorts of things that recreate the “home” experience in a work environment.

As important as the hostels is the ability to be “chaperoned” at work. In the jobs that have been “female” for decades, your trainers and classmates will also be female. You will never be in a situation where you are alone in a room with only men. And you will be less likely to be trapped in a situation where there is a man with power over you who can force you to do something, and there is no woman to whom you can appeal.

The social perception of “public” versus “private” is of course meaningless and something that you can combat by just ignoring it. But those two things I listed above, a safe place to live as a working woman and the security of never being the only woman in a room, those are very real concerns.

Thank goodness, in many cities the living situation is no longer such a concern. There are more and more places where you can rent as a single woman, and more single woman available to live with you as roommates and provide that extra security of having someone to come home to (see Pink, for example). But if your only options are renting a room in a boarding house where you just have to trust on the kindness of your neighbors for your own security, that is still a real danger. For anyone living alone, man or woman, but especially a woman.

The problem of being the only woman in the room, that is a also very real danger. And it’s not limited to India, I am certainly aware of being slightly on guard any time I realize I am the only woman. But in India, you have the added pressure of knowing that harassment or rape accusations will boom-a-rang (sp?) back on you more than on the man. And knowing that the men around you know this as well, that the only thing holding them back from doing whatever they want to you is their own conscience, no fear of social punishment.

(Not saying she is in immediate danger or anything, but there’s an added pressure with knowing you are the only woman in the room)

And this is why it is hard for a woman to be the first one to break through in a new industry in India. Because someone always has to be first. And then third and 4th and 5th. It’s pretty lonely, until you get to around 200th, and even then it’s still hard.

I’m not even talking about film yet, I’m talking about any industry. Heck, do you know how scary it is to be a woman on an IIT campus? Super scary!!!! I visited IIT Mumbai last time I was in India, and it wasn’t like I thought I was going to be attacked by hordes of engineers, it was just unpleasant, having everyone look at you constantly, being told there are certain areas you can and cannot go, having different curfews and rules than the male students.

Okay, now I want to talk about film in particular. Remember my posts about film as a family business? That means that women were always involved, they just weren’t usually “named”. Because that would make them “public women”. Saraswati Phalke, wife of Dadasaheb Phalke (India’s first filmmaker) served as his editor, his lighting technician and his co-writer/brainstormer. But to the public, her name was never known.

(Here’s Dadasaheb and Saraswati)

There’s also the social conditioning, you expect to assist your father/husband/brother/son in everything he does, without getting credit for it. And so there were generations of women behind the scenes who took care of the kids, cooked the meals, and then in the evenings went over the next day’s shooting schedule with their husband, or sat in on a narration session and gave notes on the script, or helped with casting suggestions for the various roles. But they would never have considered asking for a “producer” credit, or “writer”, that was just being a good wife/sister/daughter/mother.

There were always exceptions to this, of course. Firstly, the few women who absolutely HAD to be on set, the actresses. But they were usually kept “protected” from the messier business of filming. Shepherded back and forth by relatives, kept in isolated areas of the filming location, with a parent or brother always with them. And I don’t necessarily fault anyone for this practice, since the perception of “Public Woman” has so much slippage between “prostitute” and “working actress”, it was a safe thing to so prominently display your respectability.

And then there were the very very few women who did officially have their names listed as creators, not only artists. Devika Rani, of course, India’s first female studio owner. But even she had to come into it sidewise, only allowed in film because she had the support of her husband. Or Sai Paranjpye, female director and writer of the 1980s hit Chashme Baddoor. But these women were by far the exception, the usual reaction to seeing a female name listed in the credits as something besides an actress or a dancer was “Wow! A woman!!!!” Kind of like if you’d seen a two-headed calf.

(I love Sai Paranjpye. Here she is being cool on set with Farookh Sheikh)

In recent years, as film has become increasingly “corporate”, the ability of a woman to be officially trained and on record as a filmmaker has increased enormously. But the ability of a woman to contribute to film has decreased, I suspect. Pamela Chopra is a good example of this. In interviews she has said, essentially, “I learned about film because my husband wanted me to understand and be involved in his work.” My impression from things she has said in interviews, and Yashji himself, and other people who worked with Yash Raj over the years, is that all the highest level conversations took place in their home. And Pamela was present, and her opinion listened to and respected, because she was their hostess and it was in her home.

Now, those conversations take place in the corporate offices. Pamela has an office there, and she gets credit on films now (credit she probably should have gotten all along). But she is just one voice among many, she doesn’t have that human connection to people she would have had otherwise.

The most powerful women in the industry today are the ones who managed to straddle that divide. Zoya Akhtar, Ekta Kapoor, Farah Khan all started out as just a female relative, coming in the industry sidewise. There was a big advantage there of not being threatening (as any woman can tell you, men are like little bunny rabbits when it comes to respecting women in their profession, if you come at them straight they shy away, but if you come up sidewise and pretend to be humble and non-threatening, they will stay long enough to listen). But this also solved the very real safety issues.

(Here’s Farah and Zoya hanging out with the other top directors in the industry. Including both their brothers)

Working on a film in India means picking up a bag at a moments notice and leaving the country for 3 weeks, living in a studio for days while you finish a difficult shoot, sleeping 6 to a room when there is no money left in the budget for housing. There are no unions, no HR departments, no one to appeal to, you have to do what you are told or you will lose your job and be blackballed in the industry. All of this makes it a situation ripe for danger for women. Or, at the very least, perceived danger. You might have a hard time marrying someone “respectable” if they knew you spent six weeks travelling alone through Switzerland with a bunch of men.

However, if you are a young woman whose official job is assisting her uncle or her father or grandfather or brother, then it all has a nice gloss of respectability. And a very real gloss of safety. Zoya started out working with her father and stepmother and mother and then brother, and only then broke out on her own. Farah started assisting her uncle. Ekta ran her company for her father, with her mother as her partner.

And now all 3 of them are “paying it forward” in a variety of ways. Farah is aggressive about finding and mentoring young women. It’s not just that she is hiring them instead of hiring all men, it’s that they can apply to work with her, she is providing a work environment that is safe and respectable by being a female boss, something they couldn’t get assisting any other director. Zoya is doing similar, and Ekta is less aggressive and obvious about it, but her TV empire relied quite a bit on female workers behind the scenes.

(Farah and her team of assistants for the Dilwale shoot, plus Kriti)

Farah played a big role in opening that gap, not just because she had a blockbuster hit as a female director, but because she found a place in the new generation of filmmakers back in the 90s. For Karan and Aditya and Farhan Akhtar and dozens of other young future director/producers, it became normalized to have a woman on a film set, because after all, Farah was already there. I don’t think Farah was the only one, from the first person accounts I have read, suddenly in the 90s it started to be less “WHOA! A woman!!!!” on film sets and more “Huh, a woman. That’s cool.” But Farah is certainly the most visible success story from that era.

And now, today, we have the most powerful people in the industry ones who are eager to promote female talent. Farhan Akhtar produced his own sister’s films, and his sister’s girlfriend’s films, and also Baar Baar Dekho, which was terrible, but did have a female writer and director. Yash Raj is still weak on its female directors, but has more and more female writers working for it, and general corporate officers (notably their hotshot casting director) are often female. And Dharma productions is doing the same, no female directors so far (unless I am forgetting something), but has loads of female writers and other behind the scenes workers in increasing positions of power.

And this is where you get into micro-aggressions and so on. Ultimately, except for Ekta, the heads of all the major studios are still male. And even Ekta for some reason put a man in charge of her film division instead of running it herself. While women are more and more working behind the scenes, they still have a comparatively hard time breaking through as directors and producers, there is a glass ceiling effect in place. But it’s important to be aware that this “glass ceiling” is a very new phenomenon and only at a few studios. At every other time, and every other studio, it’s not so much a “glass ceiling” as a “brick wall”. Women are not and were not involved at all. Or if they were, it was in unacknowledged positions as wives and mothers and unpaid labor.

Now, how does this relate directly to the issue of few female lead feminist message films being made? Don’t forget that another big part of understanding how the film industry in India works is understanding the powers of the stars. “Stars” aren’t just actors. To be a real star, a major player in the industry, you have to understand filmmaking from top to bottom. All 3 Khans, for instance, have stories of changing the direction of scripts, re-editing films, and even serving as director as needed. And these aren’t stories of them playing the “Star” card and forcing their way in. These are stories of them stepping in and making the film a hit with canny and experienced advice.

This isn’t the kind of thing you learn over night. Again, just using the Khans as an example, they all made horrific decisions at one point or another in their careers. They took jobs strictly for the paycheck, they gave horrible acting performances, they picked terrible scripts. But they learned from that. Again, all the Khans have told the same stories and have the same stories told about them, they came on set ready to learn. To learn anything and everything, poking around in the costume department, the set designers, the cameraman, the dialogue writers. And after 20 years, they knew not just how to play the lead role in a film, but everything else about the entire filmmaking process.

This, for me, is the real reason Hindi film doesn’t have female stars in the same way we have male stars. It’s not because the fans don’t like them, or producers don’t give them the parts. I mean, that’s part of it, but before all of that happens, a young actress on a set just isn’t given the same kind of access and learning opportunities that a young actor is. In the same way we don’t lose our female engineers in college, we lose them in elementary school.

And so, when you are looking at a movie like Pink or Sultan or Dangal and asking “why couldn’t this just be the story of the actresses, why is there a male lead?”, the answer isn’t simply “the producer made a mistake” or “the male star insisted on it.” The answer is, “A movie can’t open without a major star taking the reins and guiding it to success, supported by a director/writer they can work closely with. There are no major female stars. There are no major female directors/filmmakers. And this is because of prejudices and social behaviors that happened decades before this particular film was even thought of, and which affected the training opportunities for women in those fields.”

If you look at the one film that is picked out from 2016 as a successful feminist female lead script, well, that’s the best support for my argument. Neerja is headlined by a female actress who benefited from the sidewise “daughter/niece/granddaughter of a filmmaker” career path. Who spent the time on set not just learning to act (or not learning to act at all, depending on who you ask), but learning to produce, to write, to edit, every aspect of filmmaking. And she took that knowledge and devoted it to getting this film made, against all odds, and getting it properly promoted and released.

(she’s pretty, and she loves her father, so she’s not threatening. But she also runs her own production house, don’t forget)

Now, my hope is that more films will come out that follow this kind of path, because there are certainly more actresses out there with the potential to be stars of this kind. Alia Bhatt, for one. She could easily follow the path of her older sister and transition to directing or producing, or else take the directing/producing training she is getting now from her mentors and turn that into reaching for top stardom. Sridevi’s daughters also have these options, and Yash Raj has started a process of “promoting from within” for its actresses, both Parineeti Chopra and Bhumi Pednakar started out working behind the scenes and were groomed for stardom. And Anushka Sharma is already well on her way.

And the tide has already begun to turn in terms of behind the scenes. Working on film is becoming an “acceptable” profession for young women. Especially coming in through ad films, which have less of an established power structure. It may take a few decades to pan out, but the seeds are there, more and more women are being accepted as part of the film community, and after several years of training, some of these women are going to be given the opportunity to make their own films.

I’ll have to read this later, as I don’t have the time now. I just wanted to ask if you can give the link to the WaPo article. But in scrolling down to the comment box, I caught the first two paragraphs, so I want to tell you that you’ve completely misunderstood the meaning of the phrase “public woman” from Guide, if it was there (I say this because the other day I was rereading your Devasas reviews, and, when you quoted from the book, I found a number of sentences and phrases that I don’t remember at all. It could be a function of the edition/translation you had, but just thought I’d note it.)

So “public woman” means a woman who is “available” to the public — here “public” usually means men, and “available” means sexually available. This does not mean any woman who is working in public, or is working to serve the public in any capacity, nor even any woman who is working outside the home. It just refers to the woman who is viewed by some men (not all, as this kind of man is definitely looked down upon) as being “public property.” So, for instance, 50-70 years ago (which is when RKN was writing), a woman who was known, or suspected, to have had an affair, for instance, especially premarital, would then be considered as “public” — since she’d given it up for one man, no reason why she should object to any other man, is the thinking. It is a derogatory term, as you can see. Another equivalent phrase is “bazaar woman” — one who is for sale. Since, traditionally, it was the courtesan class that were trained in singing and dancing to attract customers, an equivalent phrase in Hindi is “gaana bazaana type” of woman, which literally just means a woman who sings in public, but the connotation is something entirely different. In Guide, since Rosie wants to be a dancer, i.e., show off her body in public via dance, her husband or someone could have used this phrase to discourage her. Actually, I do remember her husband saying something like this for why he didn’t want her to dance.

It’ll probably be a few days before I have time to actually read your post. 🙂

LikeLike

The WaPo article is linked at the beginning, the text is in a slightly different color and if you hover over it, it should look clickable. I wish WordPress would make these links more obvious!

On Tue, Apr 18, 2017 at 11:11 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

I skimmed this post and the article quick. All good points and whenever I read these posts about why can’t the Indian film industry be more feminist or women-centric, I get a little annoyed. In the ten years I’ve been watching, there’s been great progress toward more gender equity in the scripts and behind the scenes. I don’t see the equivalent of mainstream women filmmakers like Gauri Shinde, Zoya Akhtar, and the others you’ve mentioned in Hollywood, FFS! Kathryn Bigelow is the only one that comes to mind (and the same nepotism baggage follows her around, too, because of her marriage to James Cameron). Hollywood has so many of the same problems when it comes to making blockbuster films (just ask Scarlett Johannsen why the Black Widow doesn’t have her own film in the Marvel series). You need big names to get a big-budget film made and those big names are almost always going to be men!

I’ve heard many non-Western Hindi film fans say that they find the women-centric stories that the Indian film industry is telling much more progressive than most people would expect (I think Erin at Bollywood is for Lovers makes this point often) and I completely agree. And don’t get me started on post-feminist shit like Girls, which is where I see most of the female-centric stories being told in the West headed. Today, for every Emily Blunt in Sicario, there’s a Sonakshi Sinha in Akira and Rani Mukherjee in Mardaani. And there are still tons more Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, Tom Cruise, Vin Diesel, Ryan Reynolds, Robert Downey Jr. films being made than Julia Roberts or Anne Hathaway vehicles.

Uggh, I think this topic gets me worked up for some reason! Also, I saw a stupid headline this morning about whether or not the low box office on Begum Jaan means the end of women-centric films. No, I think the fact that it was a remake of a film that those that would probably have seen the Hindi version had just seen the Bengali original and didn’t see the need to see the same story again in the theater. I think it was a miscalculation on the producers fault (and pure greed too) now that many films are being seen beyond their regional audiences thanks to the internet (duh!) and word of mouth.

Rant over:)

LikeLike

Clarification: I was ranting about the original article, not your post!:)

LikeLike

I got that, since the rant related much more to the original article than to my post!

I didn’t mind the original article THAT much, grading on a curve since I have read much more tone deaf stuff in the western press in the past. But it was a pretty simple “Hey! This film is supposed to be feminist, but the focus is on a male character!” kind of analysis. With no discussion of why a film might focus on a male character, practical reasons beyond just the writer’s prejudices peeking through.

I am less irritated by the “is this the end of female films?” articles than I used to be, because it seems like the tide is turning so much that one flop here and there isn’t going to make a difference. Noor is coming out next week, Rani Mukherjee just announced her return, Sridevi has Mom coming out, Veere Di Wedding is going to release at some point, there are plenty of female lead films in various stages of production and one minor flop isn’t going to change that.

What continues to bother me is that those flops are used as justification by the distributors! The producers seem to have caught on, they are writing and directing films for women featuring women. But once the film is in the can, it just doesn’t get the release that it deserves. That’s where the industry falters, when the businessman get involved instead of the artists. If you read the original article, he mentions Nil Battery Sonata (sp?) and Neerja as good fully female lead films from last year. But the both barely got a release! They did phenomenal box office based purely on word of mouth because they didn’t get half the promotion they deserved, not to mention limited screens.

Oh, and what I found absolutely hilarious is that there is a whole article about the male savior myth and how women should be allowed to lead their own movies, etc. etc., and it was written by a man!!!!

On Tue, Apr 18, 2017 at 11:48 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Definite irony in the fact that a man is writing that article! I agree that he didn’t go into enough depth about the industry realities and why male leads are in these films. My problem with this kind of article appearing in the Western press is that it continues a false narrative that the West is somehow superior when it comes to these issues, when I think we in the West see all the time how our popular culture continues to be influenced by problematic gender politics. Why does a film like Hidden Figures need a Kevin Costner in it to give it some extra gravitas…isn’t the stellar female cast enough? At least the author did allude to the white savior tradition in his article and the Hidden Figures situation is more a symptom of that, but definitely less so than say Emma Stone’s character in The Help.

I’m also tired of pop culture critics always having to tear down legitimate progress, instead of lauding advances and the fact that this writer is Indian and writes for elite American newspapers makes me question whether there is some kind of performative quality to the piece, i.e. I know you expect me to write articles trying to explain my country’s quirky pop culture and I’m going going to do it in nuance-free ways that you understand and that perpetuate your cultural superiority.

Agreed that the tide has turned and female-driven projects are the norm, thanks in large part to the things you mention in your post and a larger generational divide that puts the weird gender politics of say Ajay Devgan’s Shivaay or Hrithik’s Kaabil on notice.

LikeLike

Kaabil has weird gender politics? Please tell me more! I don’t want to watch it, but I want to know about it.

You articulated perfectly what bothers me most about these kinds of articles, the “performative quality”. The Indian writers who are tearing down their own culture in a quest for acceptance from the West. Which isn’t limited to just articles appearing in the Washington Post, but in the English language papers in India as well. There is no need to constantly lambaste Indian cinema for having flawed continuity, or unrealistic song sequences, or any of the rest of it. You are just trying to turn it into something it isn’t, and never was. You might as well complain that butter chicken doesn’t taste like barbecue chicken, the two things can exist simultaneously. It also means that the truly terrible version of barbecue chicken that Indian film occasionally turns out gets lauded far more than it deserves. I’m still mad at Ki & Ka, and it feels like half the critical compliments it got were really coming from a place of insecurity over the usual Indian film fare and were giving it credit only because it had sex and working women and resisted big song sequences.

At least this isn’t another article on Item Numbers, the big complaint of 2015. Because obviously, rampant sexual violence in India can all be drawn right back in a straight line to “Choli Ke Peeche” and “Sheila Ki Jawaani” (both of which were choreographed by a woman). Okay, I guess I’m still a little mad at that ridiculous tempest in a teapot.

On Tue, Apr 18, 2017 at 1:21 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

I have suffered through Shivaay but I haven’t seen Kaabil either, I must admit, based almost completely on spoilers in reviews. Spoiler alert: The wife kills herself after being raped (twice) and the husband must avenge her death. I’m just tired of these kind of stories that perpetuate the damsel in distress/rape is loss of honor/man must protect woman tropes (in any national cinema…because the same kind of tropes are in Western films, too). I think that’s why I liked Angry Indian Goddesses so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yeah, I hate that too. Although it’s a fine line, I don’t mind the suicide if it is treated as a tragedy, as yet another result of the rape. But what really bugs me is when it has the tone of “oh what fine sensibility, the woman preferred death to dishonor” and kind of lauded, that bugs the heck out of me!

Don’t know if Kaabil went with option a or option b, but considering it was a big hero lead film, I think we can assume option a.

From the side of AWESOME, can we add Alia Bhatt in Udta Punjab? Who rescued herself went on to a good life post-rape?

On Tue, Apr 18, 2017 at 2:11 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Angry Indian Goddesses! I downloaded it for my return flight from San Diego and loved it mostly. (The I am Spartacus ending didn’t thrill me, but otherwise it was a win.)

LikeLike

Joyomama, glad you liked Angry Indian Goddesses, too. It’s one of those movies I can’t stop thinking about weeks later. The ending does go off the rails with the vigilantism. I’ve heard it described as a masala entertainer for women and the ending certainly lives up to that description. I also would have enjoyed a quieter, slice of life film that centered around these women, their issues, and their internal lives more.

LikeLike

Dharma produced Gippi in 2013 and it was directed by Sonam Nair. Plus they co-produced Baar Baar Dekho and Dear Zindagi.

LikeLike

Did you see Gippi? Should I see it? I was really interested based on the trailers, and then it never released in the US so I didn’t see it in theaters. Should I track it down streaming?

Also, this is my point exactly!!!! There are female directors, they are being encouraged by the most successful and cutting edge production houses, they just are so new that they haven’t really made a major impact on the industry yet. Give it a little more time and look at the big picture, instead of just picking and choosing a few major releases to make your point.

On Tue, Apr 18, 2017 at 2:20 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Actually I haven’t heard of Gippi at all until a couple months ago when the nepotism debate was going on. Sonam Nair defended Karan on twitter saying that he gave her a chance to direct Gippi though she was an outsider in the industry.

I just saw the trailer of Gippi and it looks pretty good!

LikeLike

Right??? I was really excited for it based on the trailer, and then it never came out over here and I kind of forgot about it.

On Tue, Apr 18, 2017 at 2:35 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Farah started out assisting her aunt Saroj Khan who’s a formidable lady and is credited with making Madhuri a dancing star.As for the Kaabil furor (Disclaimer: I haven’t watched the film), Yami’s character committed suicide because she wanted to spare her husband the humiliation and pain.That was regressive.

LikeLike

Oh yeah, that’s regressive. I will continue to not watch Kaabil.

On Wed, Apr 19, 2017 at 10:06 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Pingback: Noor Review (NO SPOILERS): A Badshah Song Can’t Hide a Bad Ending – dontcallitbollywood

I loved this side of things, as in Stars are made not just by acting in good movies, but by getting to know about the whole process of filmmaking. Very important point, and one reason why actresses don’t seem as heavyweight as actors(not literally), not just because they have lesser roles, but also because they have lesser say in the filmmaking.

On a different note, this is why I love Anushka Sharma, she has different priorities than the other actresses. I remember people were skeptical when she first announced her production company, and now she has made it mainstream for a top actress to produce films just like an actor would.:) Also, Sonam is into production?!

Another promising actress is Kangana Ranaut, now that she has learnt scriptwriting and has announced her plans of directing.

LikeLike

Sonam got into production really early. She assisted Bhansali on Black before she took her first acting role, just like the male stars do, starting as AD to understand the whole process. As soon as she had her first hit, I Hate Luv Storys, she moved over to the family production house and she and her sister and father produced Aisha, a film built around her stardom. Which flopped.

She did 6 more movies in a row, and at the same time built her personal brand with all those fashion shows and L’oreal ads and amazing clothes. And then came back for another film produced by herself and her sister, Khoobsurat, followed by Dolly ki Dholi, followed by Neerja, followed by the Kareena movie she is finishing now. She’s very kind of “male” in her career pattern, taking roles in other people’s films in order to raise her profile, and then turning around and taking that heightened profile back to the family studio for one of their movies. And being highly involved in the production process, if you watch interviews with her, she is taking contract fees and distribution rights and screen count and all that stuff.

On Fri, Jun 16, 2017 at 5:23 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Pingback: Hindi Film 101: Why Do We Keep Seeing the Same Thing Over and Over Again? Risk-Reward in Hindi Film | dontcallitbollywood

Pingback: Hindi Film 101: The Three Phases of an Actress Career | dontcallitbollywood

Pingback: Another Video! Because the sun is out! | dontcallitbollywood

Pingback: Hindi Film 101 Index | dontcallitbollywood

Pingback: 2017 DCIB Awards! Best Editorial! | dontcallitbollywood

Pingback: Top 5! Best DCIB Editorials! Vote Here! | dontcallitbollywood