Another part of my boring series! Although we are beginning to get closer to modern times, the rise of piracy is something that effects us a little more directly than the original regulations around broadcast radio.

Usual Disclaimer: I have no special knowledge, this is all based on commonly available information and my own experiences.

I left off in the early 2000s, when the entertainment market looked very different between America and India. In America, HBO had ushered in a new golden era of TV when shows were made for the audience, not the advertisers. Profit was made from TV subscriptions and DVD sales, the goal was to make something the audience would be excited to see over and over again, to discuss on the new online message boards and build “buzz”, to recommend to their friends in the real world.

Something which began to be true then and stayed true until today is that the shows which are talked about the most often have the smallest audience share. At least the official audience share. Nielsen started working on a way to count TiVo’d shows and, later, shows from streaming sites. But the advertisers revolted, refused to add these new numbers into their elaborate calculations of rates. Arguably they had a point, if you were watching a show recorded you could skip the ads. But research showed that even fastforwarding an ad was still effective.

(Watch this at 3 times speed. Do you still remember what it is an ad for?)

The bigger point was that ratings were not being calculated in order to discover what the audience liked. They are quoted that way, and analyzed and discussed. Big think pieces about why good shows are less popular, why the public craves this TV over that TV, why NCIS was the most popular show in America for years and years. But the ratings are not counting the audience, they are counting the eyes on the ads. As the majority of the audience began to move away from traditional viewing, to recording shows to watch later, buying DVDs, and eventually streaming, the only audience that remained were the ones who didn’t care enough to try to seek out alternative channels. And so broadcast TV began to be the triumph of the mediocre. And alternative entertainment began to be an invisible untracked mass.

TiVo launched in 1999, the same year The Sopranos started on HBO. By 2007, the regular broadcast channels had given up on trying to avoid the inevitable, and launched their own service, Hulu, which made shows available, with commercials and for a modest subscription price, the day after they aired. The only hold out to Hulu participation was CBS, the one channel still making good broadcast ratings thanks to their identity as the channel watched by the elderly, the ones who can’t quite figure out streaming.

Netflix launched it’s streaming service that same year. They had been considering a streaming function for a while, at first thinking of a “Netflix box” which would attach to your TV. The concern being that bandwidth was still not quite there for high quality video through the internet. But youtube was launched in 2005 and already a hit, so Netflix decided that the market was ready for streaming after all. Even Netflix, the most cutting edge service, was lagging behind what the public wanted, struggling to grasp this new reality of content without restrictions. And their initial streaming offer came with its own restrictions. A limit to how many hours a month you could watch, the idea that streaming would merely augment your DVD viewing, fill in the gaps between deliveries. Especially because their streaming offerings were so limited, they hadn’t bothered to expand their selection thinking that DVDs would still be their main offering. It wasn’t until they saw the enormous popularity of the streaming option that they forced a change in company function and began to explore how they could make this whole streaming thing work.

(One of the first Indian movies they got, Andaz Apna Apna! Which reflected their strategy at the time, a few cheap cult favorites just to test out this streaming thing)

Even Netflix was surprised, because no one in the industry really knew how much content was already being watched in this way, time shifted and at the convenience of the audience. Ratings are made public, that is the standard the industry lives by. But the new counts, the far more accurate ones of DVD sales, TiVo recordings (your TiVo can send that data on), and eventually views on websites, those are often kept private. Or else made public but not immediately and not with nearly as much discussion as the traditional ratings. Maybe because this data wasn’t widely talked about, no one seemed to fully grasp that the audience now wanted the shows they wanted when they wanted them. The industry still thought they could hold the audience hostage, feed them a little bit at a time when they chose. And thus, the rise of the pirate.

The most pirated shows usually aren’t the ones on pay cable or streaming services. It’s not that the audience is trying to avoid paying a little extra here and there. It’s that they are trying to get the content that it is literally impossible to get legally. In America, that is often BBC shows, shows which are broadcast in England and discussed on online message boards, which the American fans know are out there, but they can’t get them legally until months later, after some American service has bought the rights and broadcast them and then released DVDs.

Or then there’s HBO. When Game of Thrones started and became a sensation, you could only get HBO content in America if you already had cable and then subscribed specially to HBO. Cable alone, in America, is about $60-$100 a month. HBO on top of that is usually another $20. In contrast, a subscription to Hulu is $7 a month. You could cancel your cable and watch almost all broadcast shows just 8 hours later for a 10th of the price. Considering America was in the midst of a recession which was hitting hardest the young people who were also the most internet savvy, the choice was obvious. And it also meant, in order to watch Game of Thrones and other HBO shows, you would need to find another $100 in your monthly budget and that just wasn’t going to happen.

(This is from 2014. Notice that Game of Thrones has 1 million more viewers illegally downloading it than watching it legally?)

Let me back up and talk for a moment about why this pirating and streaming was so much more important for TV in America versus movies. When the CD technology first came out, there was no thought of the fact that digital could become digital, that a CD you bought in a store could be copied on to a computer. Napster launched in 1999, iTunes in 2001. The technology was leaping ahead of legalities, is the problem. The music industry hadn’t thought to deal with digital rights, either legally or technically, and Napster found the gap. If you could rip the music from a CD, and then you could share it with your friend online, and they could share it with their friend, and on and on and on, was that any different from lending your friend a record and letting them make a copy on a cassette tape? No one was making money off of it, not directly, so was it illegal?

The music industry ended up running behind the pirates, and never quite caught up. It’s still accepted that copying a CD onto your computer, your friend’s computer, your ipod, is part of your purchase price. Not illegal at all, and if you bought a CD that didn’t let you do that, you would feel ripped off.

But the movie industry had the advantage of coming second. Simply because movies take up a lot more digital real estate than music, it took longer for computers, compact discs, and internet broadband to catch up to them. And so they launched with all their legal and technical ducks in a row. A DVD comes locked. You cannot download the content on to your computer, you cannot share it with your friends. And yes, it’s fairly easy to unlock the DVD, but then you KNOW you are doing something illegal. And the movie industry was much faster to offer digital downloads of their content, legal ones for just a small price, than the music industry which resisted and resisted.

(Even Indian film got on the bandwagon, ErosNow launched shortly after Netflix streaming became a thing. And India had been ahead of the curve on music, Smashhits became Saavn, free legal music and all you had to do was listen to a few ads)

I’m not saying movies aren’t pirated, of course they are. But they are also streamed legally, purchased, watched through subscription services, all kinds of options. You can see the whole movie for 99 cents to $4.99 legally. Or even in theaters, a movie ticket is just $10 which is still cheaper than the $100 a month for HBO. In the American market, it is TV that is the big pirate driver. One episode of Game of Thrones will have as many downloads as a hit movie will get in it’s entire lifetime.

(And now even illegal downloads are tracked. Not that these figures are talked about as much as

In the end, it was the pirates and, in a larger sense, massive audience demand which started driving the market. The people wanted streaming TV so much they were breaking the law for it. And so HBO FINALLY launched “HBONow” for a reasonable price of $14.99. Even CBS, Land of Old People, finally launched their own streaming option. And finally, just in the past year, the old technology has creaked over and you can now purchase regular TV, broadcast TV, through the internet. Everything has become one again, on your same computer you can go to youtube and watch a goofy vlog and then switch straight to a local news broadcast, and then open up a new window and watch Game of Thrones on HBO. The revolution has already happened in America, movies are dead, TV is dead, internet is king. It just took this long to become legal.

Now, let’s go over to India. The basic TiVo technology is available in India, of course, and can be hooked up to satellite TV. So that’s the same. And piracy started to grow around the same time, as DVDs came out followed by the technology to rip off of them. Not just legal DVDs of course, the ones you could buy in stores, but screening DVDs. Part of the reason reviewers of Indian films struggle to catch up is because they are less likely to be offered screeners well in advance to assist with their reviews.

What was different was the way these pirated films were spread. In America, and most of the Western world, you went to a website and downloaded it onto your computer in the early days. And then deleted it and downloaded something else. And, when bandwidth improved, you watched it streaming direct from the website. And then finally enjoyed the legal options.

But let’s look at what happened in India. The internet was less retail, and more wholesale. In 2007, when Netflix launched it’s streaming service in America, in India only 3.7% of the population had internet at all. But that doesn’t mean they had good internet, in 2009 only .45% of the population had broadband access (source here: https://www.internetworldstats.com/asia/in.htm). The internet was used to get the files from elsewhere in the world to a distribution hub in India, where they were turned into thumb drives or VCDs or DVDs. Which were then shared, or more often sold.

This was not an ideal situation. For anyone. The people making the content weren’t benefiting in anyway from this audience, either in immediate profits from them or in the ability to turn them into a secondary profit. Game of Thrones, for instance, was phenomenally popular in India. But not legally popular, which means there were no ratings to track, no statistics to site. The actors couldn’t claim international popularity when quoting rates for their next projects. HBO couldn’t try to sell legal copies for a higher rate because of audience demand. There was no proof of any of this, let alone money being made.

And it wasn’t ideal for the audience either. You had to find a source, and sometimes had to pay them, and you had to wait for someone to hand it off to you, and the end product wasn’t always reliable or high quality. It wasn’t terrible, over the years the system got modified and improved (I have bootleg copies of a few films which are actually better than the legal versions), but it wasn’t as good as it could be.

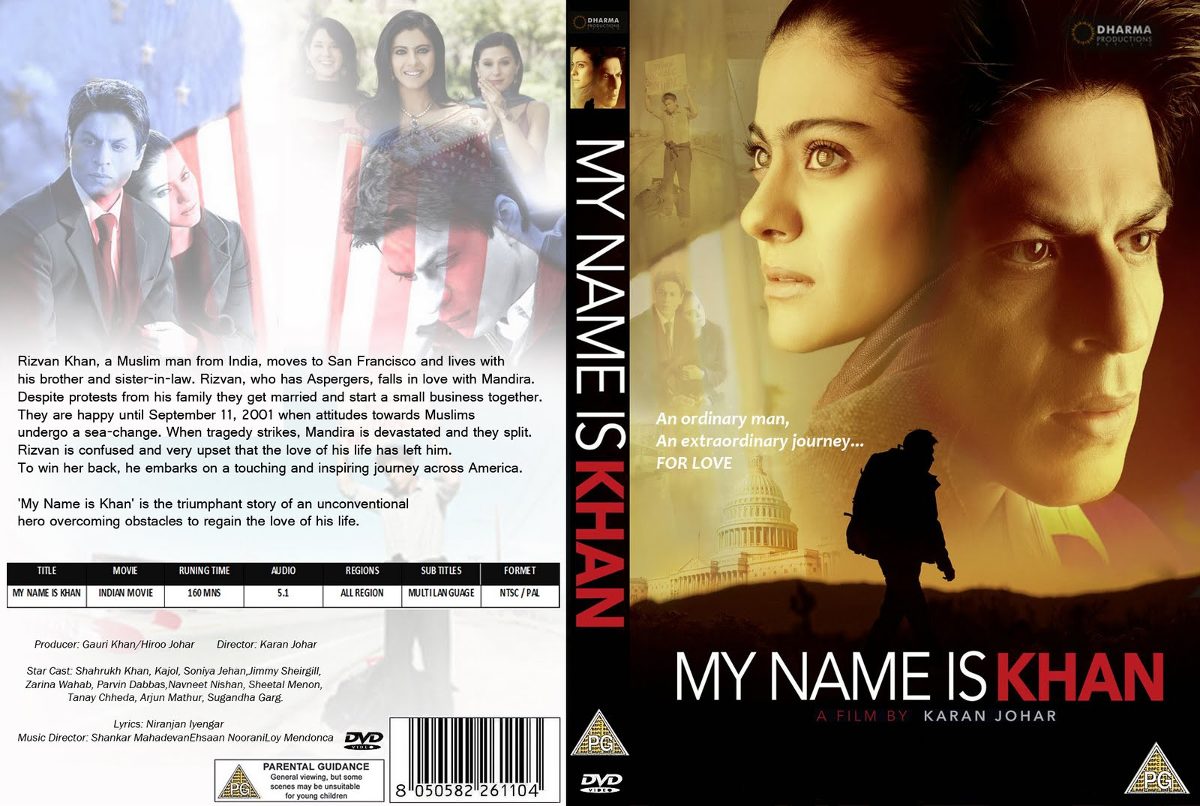

(My bootleg of My Name is Khan is far far superior to the legal one. The legal one is insultingly bad)

Another big difference was that pirated content in India wasn’t only TV, it was movies too. Partly because movies were more beloved, the audience just couldn’t wait to see them in theaters. Unlike in America, where sold out movie theaters are a once a year thing instead of once a week.

The first solution was to put those same pirated things on TV. Movies premiere on Indian television shockingly soon after their theatrical release. And the networks pay through the nose for them, knowing that they can get massive audience share for a movie premiere, watching a movie on TV being the best solution between paying movie theater prices and dealing with the inconveniences of piracy. And, eventually, TV networks started purchasing other content, what they could of the international options that were being pirated along with movies, to broadcast easily and at no extra cost into your living room.

Both these dynamics, the Indian and the America, ended up creating sudden unbreakable audience divides, walled off by technological abilities. In America, broadcast TV (especially FoxNews and CBS fiction) increasingly became a land of the elderly. The only people with the time to watch shows live, and without the knowledge of how to find better content. The youth, they became untraceable, funneling their attention to the cutting edge content only available through illegal channels, channels that were easily accessible to them since the internet was the one necessity of life you absolutely could not cut. I experienced this myself, in this era I was skipping meals because I didn’t have the money, but I never skipped on internet. Not because I just had to have my youtube shows, but because I had to have the ability to grab open shifts at work, controlled by an online calendar. And respond quickly to job ads, only available online. And email in remote jobs, and look things up for my grad school homework, and all the other necessities of my life. And if I was already paying 5% of my monthly income for internet, I was going to use it for everything I could including entertainment. And meanwhile my grandfather got up in the morning and turned on his TV and had it on all day and it would never have occurred to him to use his computer for more than checking his email once a day.

(Grandpa checks his email once a day just in case one of the grandkids emailed him something. It’s a lot of pressure on us!)

The same generation gap was apparent in India, but also a much much larger class gap. The internet is primarily in English, the ability to read English is a major marker of class and income in India. Heck, the ability to read AT ALL is a major marker of class and income. And then you add on the ability to gain access to a computer. And then for that computer to gain access to high speed connections necessary for streaming or downloaded content. And suddenly there is this very tiny group of people, young and (comparatively) wealthy who are all talking to each other on message boards and sharing files with each other and experiencing media in a completely different way than the rest of the country. And then you have another group, the women, who are sitting alone in their houses with their TV soaps on. And a third group, the lower class men who are going to single screen theaters. It wasn’t until satellite channels started aggressively going after international content that, finally, all these groups could come together again, at least for a few hours every evening, in front of the high quality prime time programming.

This is soooooo interesting. Even if I’m the only person reading this, please keep going! I’m especially curious about cell phones and access to the internet in India. Has that changed anything for the majority of the population?

LikeLike

That would be the Jio and 4G story. Security guards sitting in front of my IT work area watch ‘Big Boss’ episode for the previous day and news from Youtube channels maintained by regional news channels; Woman co-workers watch the daily soaps (missed from the previous day) on the likes of HotStar and Amazon Prime; people of my age catch up with cricket/football (English Premier League) in similar apps; youth catch up with English serials like GOT.

All during the work day. Lot of distraction – lot of productivity loss.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, one article I saw says that India has “leapfrogged” over the desktop era, especially in the past couple of years. Reliance Jio is driving down the price of data, and Chinese made cheap phones are flooding the market.

However, there is still a massive divide between internet users and non-internet users. The urban man has internet, women and people in rural areas do not. Only one in five people in rural areas (the majority of the Indian population) has internet access. And those that do have access in non-urban areas, half of them don’t access the internet daily, meaning access is probably limited to a central community computer. Even in urban areas, only 41% of women have access to the internet on a daily basis and only 36% in rural areas. College students make up 33% of internet users, followed by 26% being young men, and then 15% being non-working women (I assume housewives) and only 9% being working women (which seemed low until I remembered that the majority of working women would be household workers with lower incomes). And the cell phone era can’t make that much of a difference to them, if you look at a coverage map of India, only Reliance Jio comes close to covering the country, and it still has big gaps in the central non-urban areas. I’ll be getting into this in my next section.

On Wed, Jul 18, 2018 at 10:02 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

But the recent spate of “whatsapp lynchings” in rural India would imply that people in rural areas have whatsapp and therefore both cell phones and either internet oqr cellular access? Or is it more like a few people in a village might be on WhatsApp and they spread rumors to the rest of the village via word-of-mouth from there?

The leapfrogging is true even in the USA in poorer rural and urban communities, where they skipped the computer and laptop era of the 80s and 90s, joined in on cell phones in the 2000s, and benefited from the smart phone evolution of the 2010s. Hence social media blowing up this decade can thank its good fortune on 2010s smart phones adoption rates and cheap entry prices, and visa versa.

LikeLike

The anecdotal evidence is so different from the real on the ground evidence of internet usage, I am beginning to get a picture of communities without internet being so invisible to us that it is as though they don’t exist. So maybe an old-fashioned lynching, without whatsapp, either wouldn’t get reported because it isn’t thought of as “news”, or would take place in a community that no one bothers to cover because they are so marginalized? All the data I can find says India still has only 36% internet access, including phone internet. And that’s not the kind of thing you could get wrong, right? I mean, it’s not based on estimates and so on, there would be hard data you can look at to get those figures.

The data also generalizes down to 1 in 5 having internet in rural areas, which could mean one young man of the house has a smart phone with internet on it and communicates to other households, or it could mean one in 5 villages has really good internet and the other 4 villages are invisible to the larger world. Data is tricky.

On Thu, Jul 19, 2018 at 9:40 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Communities without internet is a fascinating concept isn’t it. On the ground, it really is the same thing as the early days of TV in India. We’ve always been very good at sharing. In school if one classmate got a walkman to school, all their friends got to listen (two kids sharing a pair of earphones). It’s the same with smartphones. Chinese phones made it into the market and a significant number of people in villages got them. Even if it was bought just for the beloved boy of the family or if the new bride brought it with her.

Also, we literally still have mobile shops that transfer content to your phone for dirt cheap prices. Like for 20 bucks, you can get the entire 90s hit songs. Movies and porn too make it to phones this way. Jio revolutionized internet usage but viewing content on smartphones by people who couldn’t afford cable/didn’t have power for a significant portion of the day/lived away from home/didn’t have internet started basically in the mid 2000s.

Even people with high speed internet and smartphones today aren’t wasting 60-70% of their daily data on downloading films or TV series. They’re using it for video calling and WhatsApp and if any data is left, they’re using it for random/trending YouTube videos. Larger files are still shared between devices.

Piracy really started with the videotape era. And again it was a mix of unavailability of the film in their town and a theatre outing having to be tickets plus food for at least 8-10 people.

It was the same with DVDs.

Streaming, especially regular streaming for like a series etc, is still rather rare. Unless you have a smart TV that can support screen casting or direct streaming, your entire family isn’t going to watch internet based content with you because again, you can’t huddle over a desktop monitor or a laptop regularly.

The problem with platforms like Viu, Hotstar and Netflix is that none of them have enough content that you can’t get on your TV. Pricing is also a big issue because we don’t have the entire weekend off. A working Saturday means you have a couple of hours before bed on weekdays, a few more hours on Saturday night if you’re not going out and Sunday to manage your social life and content viewing. Even the young urban single people living with flatmates work 9-11 hours then have a commute of at least 40 minutes in traffic or congested metros.

For the future, pricing is going to decide which platform “wins”. For now, TV and shared pirated content looks like it’s here to stay

LikeLike

For content, that’s why Netflix is looking at creating original content, trying to suck you away from the TV with something you absolutely positively can only get there.

But I bet the time is the bigger issue. In other markets, it’s all about time shifting, watching what you want when you have time. What you are saying about time, that’s not THAT different from other places where streaming has thrived. But it only works if you have multiple devices and multiple means of access. People watch on phones on the train, on their lunch hour, and then at home moving the laptop from room to room, making it more convenient than a TV in a fixed location, something you can take with you while you do laundry, prepare dinner, etc. But that only works if you have loads of data and constant internet access.

And of course the social aspect is another big part of it, streaming is meant to be solitary, structured so that it is one person starring at a phone and watching at their own pace, and that’s going to be harder to manage. Especially because it’s not just the original watching that’s solitary, it’s the discussion as well, since everyone is watching at their own pace, you can’t really talk to each other about it.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 1:23 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Maybe that’s why Ekta Kapoor’s K-series thrives so well. It gives their primary audience discussion material for which they don’t have to leave their established social setting

LikeLike

Now I’m thinking about it, really what that audience needs is something slightly lower quality instead of slightly higher quality. Right? you don’t have to pay close attention because everything is repeated three times, and all the plot points are semi-predictable. And you can discuss it with your friends without needing to have specialized background understanding of the philosophical underpinnings or historical background or any of that, it’s just human nature simplified.

Netflix and Prime and the others, in their original content, have been focused on making something better than what you can get in other sources, but what would drag in the audience in a crowded shared space is something slightly worse, something that you can enjoy more if you watch it while being just the slightest bit distracted. Which is my problem every time I try to watch a Hindi soap, I am focusing on it too much and it is truly unwatchable if you give it your full brain.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 9:10 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Netflix and Prime want to recreate their western model of success in India. That’s never worked for anyone. We got McDonald’s but no outlet in India serves the western menu. You gotta McAloo Tikki it if you’re thinking of being accepted by the Indian audience. Look at what companies like TVF, EIC and AIB are doing. They’re making videos and series that you watch and share a link to. And they’re getting rich off it. Off their own original content that clicks massively with the young urban crowd.

LikeLike

Maybe Netflix and Amazon should be going more for recreating the youtube effect? Like, if Superwoman got her own Netflix show and the first 6 episodes were offered for free on youtube, I could see that getting shared and talked about and drawing in viewers. Sure most people would just watch the free stuff, but at least some of them would pay for the Netflix version and talk it up.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 9:28 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

YouTube is only working because of the freebies. At any rate, the indian market is massive. Also, massively broke. You’d need a really original marketing plan if you wanted to break into the rural market. Like high quality rural language (as opposed to standard urban regional language) programming. Think like a 6-7 part miniseries in pahadi about a village girl that got possessed when a deity visits, a Bhojpuri show around chhath puja (there’s a reason why Nadiya ke paar was a cult hit), a Punjabi show about a land dispute and kids that are desperate to go abroad.

Start with these, with programming in local languages that feature local artists and local culture and local songs and rituals. Shoot on location to get the buzz among your target audience. You can’t win India with a blanket strategy for the entire country.

LikeLike

Yep, that’s the other problem, the streaming systems seem to be only connecting with the Hindi industry. Even just looking at what is offered on Netflix, there is a ton of Hindi, it’s the default. And a growing number of Malayalam. But very little in any other language, especially Telugu. I can see not wanting to bother with buying more Kannada films, for instance, if they are trying to attract the NRI audience, because the Kannada speaking percentage of a non-Indian country is going to be very tiny. But if they want to break into India (which they are outright saying they do), then they need to figure that out.

Maybe just filming multiple versions in multiple languages would be the solution. Only have one high quality story idea, slightly change the costumes and set to reflect different regions, and translate the dialogue. Or just have one story set in an urban area where the differences would be less noticeable and dub it.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 9:50 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

How would they account for regional differences though? Besides, our films are already doing the dubbing thing. It’s popular but you won’t buy a subscription for it.

LikeLike

Maybe do the Gautham Menon thing and film simultaneously with different casts in different languages?

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 10:12 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

It would just make more sense to make different stories altogether than managing something like this! Especially since the USP of local content would be, well, region specific cultural nuances. And we already have plenty of amazing desi writers whose works can be adapted

LikeLike

I think AltBalaji is quietly heading in this direction. Which goes to another commentator’s guess, that they are shooting for getting good enough and popular enough to be bought out for their content library.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 11:33 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Balaji of course has the advantage of their existing TV presence. They’d be stupid to give up that space

LikeLike

Another alternative for them would be to leverage their power and existing streaming channel to force Hotstar to pay twice, once to broadcast and once for special partnership with their streaming. It’s what ErosNow managed with Prime, their content is still branded “ErosNow” even through the Prime portal.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 11:48 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Which would make Hotstar even less profitable

LikeLike

Well, then they can do the r-rated Draupadi show that I am selling them, and make all the money they need in a week.

5 street kids who swear eternal loyalty to each other and to always share everything? Rise up as gangsters and enter a competition for the local young prostitute? Who ultimately ends up controlling and ordering them around, while being married to all 5 of them simultaneously?

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 11:52 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Better idea- you make a series about this ambitious young Lahauli girl who dreams of getting out of her desolate Himalayan village and go study medicine at Solan and live the hip life. A tragedy and an old promise forces her to marry five brothers. It’s not weird because that still happens there. Her oldest husband is nearly 20 years older than her and the youngest is barely 12. How does she navigate this brutal tradition and can she escape the life of gloom that awaits her??

Plus, all of this would be shot on location with backdrops like these

LikeLike

But if I am a young urban woman with disposable income, I don’t want to use a streaming system to secretly watch a story about a village woman trapped in a marriage! I want fun sexy times in the city.

Of course, I am a young urban woman with disposable income in America, maybe yuwwdis in India get off on the more depressing tales.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 12:17 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Except village women and village men and village kids in Himachal have enough apple money to buy new Nike gear every year. And they’re very proud of their culture. They’re the ones that’ll pay a subscription for this series because it’s the hip new thing and it’s about their culture and it’s in their language

LikeLike

Oh yeah, that makes sense.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 7:14 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Or better yet, Netflix and Amazon and Hotstar need to launch their own TV channels in India and offer content there and get rich off ads like all others

LikeLike

So, reverse engineer the Hulu effect? Hulu started as a free streaming source for the same shows you were already addicted to from broadcast TV. And then they slowly added to their library and also added a fee if you wanted to access on multiple devices etc. etc. And finally a higher fee if you wanted to avoid ads. So if Netflix and Amazon started by putting content on TV with ad revenue, got everyone addicted and used to that style of content, and then offered a streaming option (still with ads) for free, got everyone addicted to that, and finally started adding on fees to avoid ads, to watch more than 20 hours a month, etc. etc. etc.? The goal would always be streaming not broadcast, but they could use broadcast to draw people in until the got them where they wanted them.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 9:31 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

There could be two levels of it– high quality family friendly content for TV and the R rated stuff for their streaming platform. Indian boys will give their left arm for that lol

LikeLike

Speaking of Indian boys, another issue might be understanding what non-Indian content appeals to them versus to American audiences. The Batman series, for instance, was very successful here but isn’t one that is so beloved as to inspire you to sign up for a streaming service just to watch it. But my impression is that for the Indian male youth, it might be.

Hotstar has that data and knows it’s audience, but Netflix and Prime actually have the rights to those films and just don’t know to promote them.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 9:41 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

With the kind of money they’re spending on acquiring rights for non-indian content, they can make R rated originals of their own. Tailor made for indian boys. And girls.

LikeLike

An R rated reboot of Draupadi’s romance with the Pandavas would be wonderful, wouldn’t it?

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 9:54 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Do you want this country to burn, Margaret??!!!!!

I was actually thinking more like American Pie updated for engineering students lol

LikeLike

I don’t know how to hop into this conversation so dropping this here: what about giving local artists the equipment to shoot very low budget series and then distribute via the streaming services? The cost to the services will be almost nothing, they could market it as an emerging filmmakers series or something like that, the local stories will be told with the local cultures preserved. Low costs, low pressure to grab a massive audience but you’d still reach enough people for the services to want to offer it. The creators would have to get very involved in promotion but it would be promoting to their own community. I’ve seen some low budget YouTube series that are wonderful, for example, Much Ado About Nothing modernized and set in New Zealand with a cast of teenagers, all shot in people’s houses and outdoors with simple video cameras. It was successful enough that they shot a sequel.

LikeLike

That’s already happening. For example, check this new release in Telugu on Viu app – https://www.viu.com/ott/in/en/hindi/playlist-pelli_gola_2-playlist-25573532

LikeLike

In fact, it is backed by a big studio, Annapurna Studios (Nagarjuna’s)

LikeLike

Let me flip it. How about exploring the local industries that, in most places in India, already exist? They just aren’t as promoted and well known as the bigger ones. The streaming services can give them slightly better cameras and a guaranteed outlet for their movies once they are made. Something like Lucia, or Angamaly Diaries, is already almost guarrilla filming, they were made on such tiny budgets, and without streaming support. Reach out to the people already making these movies, and give them an advance on their next project and watch what happens. And then promote the film as locally made and a rare gem, instead of letting it disappear into the mass of content (“An Off-Day Game”, already on Netflix, was shot like this and I only know about it because I dug through every Indian film in their library).

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 11:45 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike