I hope a lot of you watched this movie. It is worth watching, and it isn’t immediately intriguing. The filming and acting style is oddly stagey and direct, and the topic is hardly appealing. And yet, it has a power that no other film quite does.

There are a fair number of Partition movies that deal with big movements, the great men of history making big decisions. There are other movies that deal with spectacular heroic personal stories, the unrealistic imaginary personal fight and triumph. But this is a film that never moves beyond the small world of one village. These people did not go on to be famous or important, their suffering and heroism was never celebrated, or even remembered by anyone besides themselves. And that is part of it, that this kind of suffering is so universal there is no one you can even go to for sympathy. My friend’s father lost his sister, but that was just one of so many losses. Their family was one of 1 million people who arrived in Delhi in 1947, doubling the population of the city. And her lost aunt was one of 2 million people lost in the course of the migration. This movie understands that, understands that these characters are living in a world where their suffering is an every day universal event. The big moments are not filmed as “big moments”, they are simply what happened, to these people and to so many others.

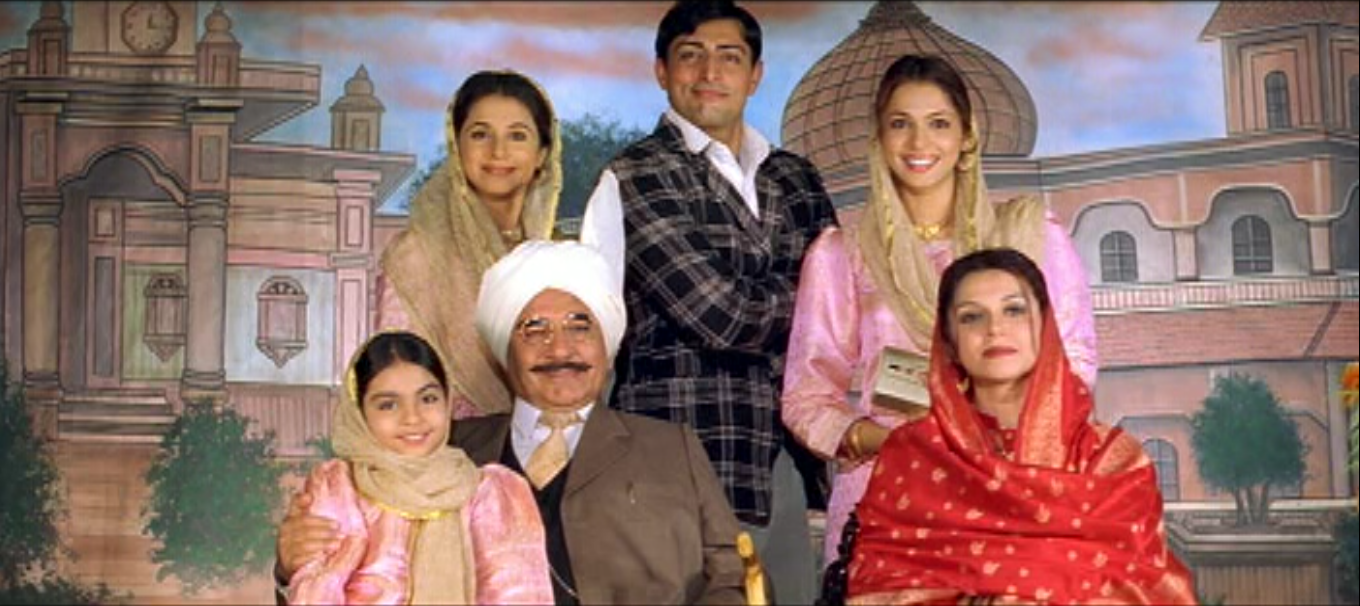

Part of that small flavor is in the casting. Each actor does a wonderful job, but none of them are big names. The biggest name is Urmila Matondkar as the lead. I was unimpressed with her performance at first, it felt more “filmi” than everyone else. But as the film went on, I came to appreciate what she was doing. Her character starts as shallow and simple because she was shallow and simple. But then she enters a different part of life, of her story, and she becomes silent. Urmila’s performance gained depth as the character gained depth.

Manoj Bajpai has the most difficult role, harder even than Urmila’s. And again, I was unimpressed at the beginning. He seemed to be playing the usual stalker-lover-hero type. But as the film went on, he also became increasingly still and silent. The silent man who acts with his eyes is much harder than the passionate lover at the beginning.

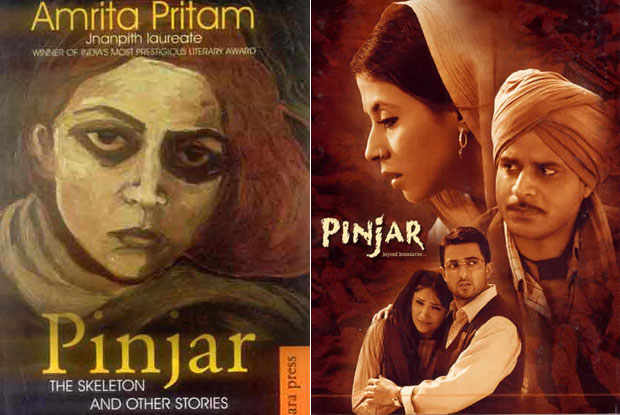

But the real star is the story. This is a story written as the wounds of Partition were still open and bleeding, written by a Punjabi woman who witnessed what happened to her fellow women all around her. There are no easy answers here, no sentimental romantic version of a woman’s life, it is the stark reality of disappointment, acceptance, and finally hopefully peace.

SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS

The basic plot of this film sounds impossible and wrong. Urmila is a young Sikh village girl. She is kidnapped and raped by Manoj Bajpai, member of a Muslim family that is feuding with her own. She escapes and returns to her family home, where her father sends her away because she is shamed. Manoj marries her and keeps her with him. She spends two years with him, resisting his touch, living a life of drudgery, never seeing or hearing from her family, forced even to change her own name. She dreams of her Sikh fiance and the life she could have had with him, a life of wealth and education and ease. Her brother, who does not know that her parents turned her away, keeps looking for her. At the end of the film she is reunited with her brother, and her Sikh fiance who is still willing to marry her. And instead she turns away and chooses to stay with Manoj, her rapist, and the life of hardship he offers her.

A woman choosing to stay with her rapist instead of return to her family? Why would you want to tell this story? Amrita Pritam (the author of the novel) wanted to tell this story because it was a story that was happening every day around her. During Partition, thousands of women on both sides were kidnapped from their families and raped. After Partition, the Indian and Pakistani governments agreed to a process for returning these women to their original families. Out of the estimated 33,000 women kidnapped into Pakistan, less than 10,000 chose to return to India. Out of the estimated 50,000 kidnapped into India, only 20,000 chose to return to Pakistan. This is a reality, and it is a story worthy of being told, without judgement.

It’s not a unique story to Partition, or even to India. There is a natural human instinct to cling together, to love, to form families. If a person is removed from their home, even violently, and placed in a new home, they will adapt. There’s a children’s book I read that stuck with me, based on a true story, about Mary Jemison. During the French and Indian war in America, when she was 11 years old, her entire family (including her baby siblings) were killed and scalped in front of her by Native Americans. She was taken captive and traded and eventually given over to a new family of the Seneca tribe. This was a common practice among some Native American tribes, the idea being that the war captives are taken into families in order to replace the war dead. There is a kind of beauty to it, you lose a son in the war, and the enemy provides a new son for you. Mary adapted to her new life, learned a new language, and slowly bonded to her new home and new family. She was discovered by Europeans eventually and offered a chance to return to a White world. And she refused it. She spent her life acting as a go between for her tribe and the Europeans, married twice (both Native Americans) and raised 6 children. Mary Jamison was given the choice between trying to go back, to return to the live she had before her capture, or going on with what she had and where she was now. And she chose to go on.

That is what this story is about. How you have to survive, and in order to survive, you have to accept, and grow, where you find yourself. And sometimes you grow so far, you can’t go back. In this story, it isn’t just Urmila and all the other women like her, it is the whole country, the two countries, that grew so far apart they couldn’t go back.

Beyond the basics of the plot, Urmila’s rape at the start and decision to stay with Manoj at the end, the rest of the film goes in a lot of directions. There is no clear connection of any of them. But that’s life, things just happen to you, and they change you, and there is no greater meaning than that.

Manoj takes Urmila away from their shared home village to a place where he has more family. Urmila is pregnant by her rape and miscarries. It is painful physically and emotionally. Manoj at first is happy about the pregnancy and cannot see why she is not happier. He still has a confused vision of them as a “normal” couple. Her anger and silence towards him even in this moment help him to see what he has done to her. Her physical pain during the miss-carriage helps him to understand how much he loves her. And her silent suffering through her feelings helps her grow, helps her learn to be stronger.

He has a hard time remembering to call her by her new Muslim name, and so forces her to have it tattooed on her arm. She scrubs and scrubs at her arm but cannot wash it off, he watches and does not understand. His family welcomes her and supports her, especially after the miscarriage. They ask her to travel to a Saints home near her home village and she dreams of seeing her fiance. She meets him and speaks a few words, but no more. Shortly after, her brother comes to the home village and suspects that Manoj is the one who took her and burns his fields. Manoj returns home but refuses to file a police report for the field burning, orders his family to let it go, and returns to Urmila and honestly tells her that her brother probably burned the fields but he will not file a police report, he understands why her brother did what he did.

Urmila and Manoj find a baby next to its dying mother and take care of it, the village leaders want to take the baby away, Manoj speaks up on behalf of Urmila, not wanting her to lose the child. The baby is taken away anyway, Manoj comforts Urmila. Urmila finds a woman in a field, escaped from her rapists, a Hindu refugee. Manoj and Urmila hide her and Urmila takes her to join the refugee camp. Urmila meets her fiance at the camp and learns that his sister (her sister-in-law now, since she married Urmila’s brother) was taken by raiders and begs her to try to find her. Urmila and Manoj plan together, Urmila acts as a spy, pretending to sell sheets and visits every house until she finds her sister-in-law. Manoj waits outside to take her (as he took Urmila all those years ago), risks his life to save her and then hides her in their home.

It is this last story that is most important. The film, and Urmila herself in describing what they are doing, put it as a way of telling Urmila’s story over again, but with a different ending. Urmila suffered two tragedies, first her kidnapping and rape. And second, her family rejecting her and sending her away when she returned to them. This woman, her kidnapping and rape was the same, but different because this time her family would not reject her. Partition, strangely, “saved” some women. This disaster was so common that it was no longer a shame for the family. The world had changed, a woman could return home again after being taken and be accepted.

This kind of kidnapping and rape is different from the version we usually see. In the Hollywood version, often “rape” is done at random, by a stranger. It is a crime of opportunity. Or it could be done by those closest to you, someone obsessed over you in particular. In both cases, the rapist does not have any need to advertise their crime. The goal is the act itself, once it is done, they do not wish to speak of it. But the rape shown here, and in other films, the goal is for it to be known, it involves two entire families. The woman is taken and held away from home in order to bring shame to her family and triumph to the family of those who took her. What happens to the woman after that does not matter much. This kind of raiding happens all over the world, any time civilization breaks down, from gang warfare in urban areas to rural land feuds. With Partition, it was played out on a massive public scale, the refugees traveling through the border regions became elements in an enormous “game” that was won by taking the women for your side. When Urmila was taken, it was just a few people in two families playing winner-loser with their women. But two years later when her sister-in-law is taken, it is two countries playing that same game.

Manoj himself was only one part of this game. He raped Urmila because his uncle ordered him to. He kidnapped her for the same reason. It was not because he individually wanted to do this to her, it was because of a bigger pageant they were playing out. The story of the film is Manoj coming to terms with his role in that pageant and breaking away from it. It starts with him following her when she escapes, waiting for her to be rejected by her parents, and then taking her home again. His team has “won” the game as soon as she is turned away by her family, her family accepting their same and loss. He could have left her to kill herself, but instead he takes a step out of line and saves her. He marries her, and immediately suggests they leave this village. He takes her away to a new village, away from his uncle who ordered him to rape and to new relatives who will love and accept her, giving them a chance of a fresh start.

Manoj in the film speaks of his “sin” a lot. The story is of he and Urmila coming to turns with this event that defined their life, finding a way to build something beyond and outside of it. Urmila learns how to move on from it, that she is stronger than she thinks. And Manoj comes to see, with every passing day, more and more deeply the wrong that he has done and feels the growing weight of how he must atone.

The film leaves it to us, the audience, to judge much of what we are seeing, the complications built in to the situation. Sanjay Suri (Urmila’s fiance) is the man she “loves”, the one she dreams over during her time with Manoj. But they never speak during their engagement, her only interaction with him is a brief glimpse as he passes in a field. Urmila claims to love Sanjay, but she does not know him. All she can love is the idea of him, of everything he represents. Her safe world, her familiar dreams, the security and wealth and familiarity of his household. When she meets the reality of him, in a refugee camp with nothing and no one, she barely reacts to him. Her “love” was not love at all. Her life with Manoj, her hard unromantic life, that is love. It takes just a moment of truly considering leaving him for Sanjay to realize how shallow their connection was. Urmila was in love with the idea of the life she could have had, more than she was in love with Sanjay himself.

There’s also the class element. In a previous generation, Manoj’s family lost their land to Urmila’s, leaving them in poverty. And taking advantage of the situation and their inability to fight back, Urmila’s family kidnapped Manoj’s aunt and raped her and returned her. Now, while Urmila and her family live in their large houses and study law and poetry and talk about freedom for the country, Manoj’s family lives in huts and struggles to survive day by day. Urmila loses not just her family and community in this marriage, but her class position. Instead of being the pampered sheltered daughter in silks and lace, the one who sings and dances through her days, she becomes a working farm woman. Urmila dreams of her other life but we, the audience, see how in some ways this new life is better for her. She learns the real value of hard work, and of her own hard work. She is valued, as herself, by her new family. Manoj’s relatives care for her during her miscarriage and after, they visit and teach her, and they respect her so much that his elderly cousin asks her to travel with her and take care of her over her own daughter-in-law. It culminates when she returns to the original village to save her sister-in-law. Before, she was a shy insecure young woman who was kidnapped from a field. Now she is the rescuer, with her new position as a working class woman she is able to travel house to house, talk to anyone and do anything. Marriage to Manoj gave her strength, and security. She can take care of herself now. Meanwhile, her sister-in-law who has all the privileges of wealth, is left to be taken and tortured, helpless.

It’s not so much that the lower class life is freer and better for a woman, it is more that the upper class life is no guarantee of security. What goes unspoken is that if Urmila had married Sanjay Suri as intended, she would have been with him while he fled his home and all his lands, she would have been the one taken (not his sister), and she would have ended up suffering terrible torments after all. Amrita Pritam in her novel, and the makers of this film, had the option of the flight being from Urmila’s family home, not Sanjay’s. But they chose to have it be centered around Sanjay’s home and family, the home that would have been Urmila’s had she married him. The lesson is there to be seen, class and wealth are no protection for a woman, the best protection is self-reliance. Going back to India at the end of the film is no guarantee of a better life than staying with Manoj, marrying Sanjay and having her wealthy perfect life was no guarantee of safety either.

And then there is the questioning of the “heroes”, the other non-rapist men in the world. Alok Nath (Sanjay Suri’s father) is the peaceful one, he would rather remain passive and confident in his own power than move. His wife and children end up fleeing their home minutes ahead of looters while he is lost into the sea of Partition. Kulbhushan Kharbanda, he is not a rapist either. But he drives off his own daughter in order to protect his reputation in the community. Priyanshu Chatterjee (Urmila’s brother) and Sanjay Suri, they are the men of the younger generation. They are supposed to be better. Sanjay refuses to marry if he cannot marry Urmila, remains faithful to the promise he made her instead of pretending she never existed. Priyanshu will not forget his sister, even when his father tells him to, insists on searching for her and filing police reports. The older men are obviously not perfect. But if we look at the result of their actions in the narrative, there is a question if even the younger men are truly good. If they are still seeing the world through their own blinders.

Priyanshu burns Manoj’s fields. That is his grand statement about his sister’s kidnapping and rape. He knows the man who probably took her, but he doesn’t try to track them down and find his sister. Worst of all, he does not pause to consider that burning the fields will harm Urmila along with Manoj. It is one of the few times the subtext becomes text, when Urmila responds to learning about this by asking “did he not think about what it would do to me?” Priyanshu also responds to the loss of Urmila by shutting out his wife. It is an understandable sympathetic human thing for him to do, but it is a flaw. He is once again putting his own feelings over that of a woman, focusing on his loss and missing of Urmila over the needs of his wife who is in front of him. And again, subtext becomes text, at the very end Urmila orders Priyanshu to think of his wife as her, to treat her as he would treat Urmila were she to return to him. To look past his own injured pride and pain and think of the people in front of him.

There’s also the question of how different, exactly, are other marriages from Urmila’s marriage to Manoj. Urmila’s marriage starts with a kidnapping and rape, that is different. But after that beginning, she is still learning how to live with a stranger, adjusting to life in his household and with his family, like any other traditional Indian wife. She is one of 3 young women married at the same time. Priyanshu marries and takes his wife (who met him once prior to marriage) from her village home to the city. He does not talk to her or spend time with her, so sunk in missing his sister he cannot see his wife. She is left to adjust as best she can and is excited when she has an opportunity to return and visit her own family. Urmila’s sister marries as well, a cousin from the village, and goes to London. She is also taken away from everything she knows and told to forget her former life. Early in the film, before the kidnapping and rape, Urmila and the women of her family sing together a lullaby, asking why mothers are asked to say good-bye to their daughters. Woman are raised expecting to marry a stranger, leave everything they know, and learn to be happy. Urmila was conditioned to accept what had happened to her, and her family and society were conditioned to accept a daughter who is suddenly just not there. Maybe the family “honor” was harmed by the manner of Urmila’s marriage, but if she had been raped by the man her father chose for her in a socially accepted way, would her family even have cared? Or noticed? The answer most likely is “no”.

Urmila’s marriage begins as the only slightly darker version of other marriages, forced to be with a stranger, to say good-bye to everything she knew. And as it goes on, in some ways her marriage is stronger than the others. Unlike her younger sister, she is able to stay in India, cooking the same foods and singing the same songs and walking the same fields she has always walked. Unlike her sister-in-law, she has a husband who talks to her and cares about her needs above his own. Again, the story does not say this to us, but there is a reason we are shown Manoj speaking to the village elders and begging for Urmila to be allowed to keep her baby in contrast to Priyanshu’s wife trying to get any moment of attention and interest in her needs from him.

There’s a lot in this film, but primarily it is a story of survival. In the West, it is accepted now to refer to “rape survivors” rather than “rape victims”. It strengthens the survivor tells her/him s/he is strong and right, and reminds her/him to be proud of surviving instead of ashamed of being a victim. But it is also accurate, you survive rape every day, every day that you choose not to kill yourself, you choose to go on living. In Indian films in particular, rape is the end of things. A woman is raped, and she kills herself. Or is killed by the rapist. It’s tidier that way, easier than dealing with the reality of a suffering living woman. It’s glorified even, set up as the feminine ideal. A truly virtuous “good” woman would put her honor above her life. If you survive, you should not be proud, you should be ashamed. You should have fought back so hard that they had to kill you, or you should have felt such great shame that you had to kill yourself. In fact, it retroactively becomes not-rape if you do not kill yourself, your lack of shame shows it was consensual after all. This film deals with the awkward reality that yes, women are raped every day. And yes, many of them survive and learn to live with their rape and their rapists. We shouldn’t judge them or pity them, we should admire their strength and respect their story.

I wish Prosenjit Chatterjee was in this film but sadly it’s Piyanshu Chatterjee!

While Rashid abducted Puro, he didn’t rape her while she was in captivity (there’s a specific line during the scene before the marriage where Puro said that all she did was drink his water and eat his food) but of course society wouldn’t believe that (much like Sita’s trial by fire which the movie has a song about in the beginning!) so they assumed it happened. Ironically, the rape happened after marriage which sadly society does find acceptable. I think what makes the situation more complicated is the fact that Puro’s parents outright rejected her when she went back to them before her wedding (the scene almost feels like some sort of perverse blessing to a marriage) and after Puro gets married she isn’t treated as a hostage but as an actual family member. She forms relations with the women of Rashid’s family and they all support one another. She makes a life there and learns to adapt. Rashid is such a tricky character to have and is just so easy to mess up. While he abducted her out of family pressure and most likely mistook her general passivity post-marriage for genuine acceptance, once he figures out that she truly despises him he does back off and gains a self-awareness of his actions. This and the fact that Rashid constantly guilt ridden (Manoj did an excellent job conveying this) is what really allows the audience to accept him as a character.

As fascinating as these two characters are to me, the true standout of this film really is the story and how it connects Puro’s own tragedy to the larger tragedy of the partition along with the general plight of women. Love the way how the movie parallels Lajo’s story with Puro’s story. Society’s concern over the “purity” of women becomes meaningless when destruction on that wide of scale occurs. Honestly I can talk about this film for days and I’m happy you reviewed it.

LikeLike

Thank you! Fixed the name thing now.

And thank you for commenting! I feel like I could talk on and on about this movie too, and yet hardly anyone has even read the review let alone commented.

You are so right about how Puro is accepted into Rashid’s family as his true wife, not as his captive, making the situation complex. Did you catch that Lajjo was too, only in a household that had no love or respect for the wife/daughter-in-law role? Her captor’s mother referred to her as “daughter-in-law” and ordered her around, her husband seemed to see her as just a body to rape. If Lajjo had been married into the family instead of captured, would they have treated her that differently? In the same way that Puro was treated the same as if she had been Rashid’s respected chosen wife, would any daughter-in-law taken into that household have been considered just a slave and a body?

Rashid is the only male character who, I think, really gains that awareness, maybe Priyanshu at the very end too. Alok Nath and Kulbhushan never seem to consider how their actions affect those around them (Alok deciding his family will stay and opening them up to violence, Kulbhushan exiling Puro without discussing it with Lilette Dubey). And even Sanjay Suri and Priyanshu, the “good” ones, are more focused on their own pain than on what they do to others, Priyanshu burns Manoj’s fields and ignores his own wife, Sanjay does not make an effort to save Puro and assumes she will still want to marry him at the end of the movie anyway. Meanwhile Manoj from the start is wracked with an awareness of his own power and desires and the damage they have caused, and that awareness grows and grows as he continues to put the needs of his wife over his own.

LikeLike

I don’t remember Lajjo’s captors calling her daughter-in-law huh. If she did marry her captor I honestly don’t think they would treat her any differently. The reason why Puro was treated well was because she was surrounded by people that did want to care for her.

As for the men, I honestly really don’t sympathize with them (Trilok in particular) apart from Rashid and maybe Ramchand. Trilok’s search for Puro always reminded me of those rape revenge films where it’s always about the man’s own honor being destroyed and I absolutely love how this film actually showed how selfish and harmful he was being by being only concerned with Puro. And considering how he burned Rashid’s fields and stopped his search after that, I really can’t help but feel like revenge is his top priority. He tells Puro that he’ll treat Lajjo better in the future but honestly….I kind of don’t buy it (or maybe the way how Piyanshu delivered his line here was an issue idk). As for Ramchand, in the book he actually didn’t wait for Puro and married her sister so the creators of this film obviously wanted Puro/Ramchand to be a bit more of a possibility here and make Ramchand more saintly but despite that choice, I just don’t think he was that into Puro in the first place which makes sense because he never met her! The main reason why Puro’s infatuation with him last as long as it does is because to her Ramchand is a fantasy and is representation of a happier innocent time (interesting that it all stops once she gets closure by actually meeting him at the fields). Contrast this to Rashid who despite completely ripping apart her previous life, is actually there and actually knows her. Honestly, take away the abduction and the beginning and the way how their relationship plays out is very much like a regular marriage from the time. And once Rashid fully realizes that Puro still despises him, he gives her space and accepts the possibility that she may never love him. If he didn’t do this I honestly don’t think Puro would have ever warmed up to him.

Something I’ve found interesting about Rashid and his connection to his family is just the contrast he has with his Uncle and Aunt. Whenever he is at his uncle’s house, he always seemed incredibly uncomfortable there (also the fact that his cousin excitedly volunteered to carry out the kidnapping instead is what pushed Rashid to action is a detail I’ve always found interesting) while as soon as he moves to his aunt’s village he just seems happier and freer in general. Furthermore, when it came for the generational feud, I’ve always gotten the impression that Rashid may have been one of the few men of the household that viewed his aunt’s abduction as a tragedy instead of an insult to family honor. Because of all of this, him having a self-awareness of how harmful his actions are is not surprising at all.

LikeLike

lmao I sent this too early so I forgot to write my name

LikeLike

Thank you for mentioning Rashid’s family! One thing I noticed was how very small his family was, especially compared to Puro’s. Which I read as a sign of class and wealth. Puro’s family can afford many children, can live easily and live long. We see her mother having yet another baby while Rashid’s family is struggling and it seems to be just him, and his cousin, and his uncle back in the home village. And then in the second village, they have more relatives, but still so few that they are eager to welcome and appreciate Puro and Rashid as new members. It makes life harder for them, they have their small house and Puro is working all the time. But it also gives them a closer bond, while Lajjo and Trilok could lose each other in the big house filled with relatives in Amritsar, Puro and Rashid were living on top of each other.

You are so right about Trilok and his revenge fantasy!!!! He wants to make Lajjo feel bad about Puro (who she never met), and he wants vengeance on Rashid, but he doesn’t necessarily want to actually find Puro. An interesting comparison is how Puro searches for Lajjo. She spends days going house to house fearlessly. She comes up with a plan, and Rashid helps her, and they save her within weeks (or days?) of when she is taken. That’s how you look when you really want to find and save someone, not when you are half afraid of what you might find. Maybe that’s part of it? Deep down, Ramchand and Trilok were afraid of dealing with what had happened to Puro, just like her father was, deep down they felt shame and it made them hesitate. While Rashid was living in his own shame, and brave enough every day to face up to what happened to Puro and how she was dealing with it.

LikeLike

Also because they are poor they probably don’t have the wealth to have a big mansion with a huge joint family. The fact that Trilok didn’t search for his wife while his sister who never met this woman (though I suppose she did feel and obligation since they are sister-in-laws now) did honestly made me kind of hate him! Also the fact that Laajo was under the impression that there was nothing for her to come back to and was so ready to stay with Puro despite being married is really concerning

LikeLike

I guess Lajjo learned the lesson of how her family treated the “disappeared” woman through what happened to Puro. Never mentioned, a story invented to say she died, mourned but not looked for.

I guess it also goes back to the theme of women being trained to adapt. Lajjo was handed off to a stranger at her wedding, spent 2 years never really connecting with him, went back to her home (did you catch how happy she was about returning to her home? A sign that she hadn’t really settled in her new house), then was kidnapped into a torture household, and finally freed from there and taken home by people who seemed to honestly care for her. It might make sense to want to just settle and start over again, she’s already done it twice. The same way Puro was taken from Amritsar to the home village, then expected to marry Trilok and leave her home again, and instead ended up with Rashid and figured out a way to put down roots with him.

LikeLike

I will remember about this movie next time when I will be in a mood for something serious.

LikeLike

It is really very good, and an interesting watch. When you watch it, you can always come back here to talk to me about it, I still have so much to say.

On Fri, Apr 12, 2019 at 2:13 PM dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

I have only seen this movie once but read the story multiple times but it has been a while since I last read it. Your review has made me want to re-read it. Somehow reading feels less emotionally taxing than watching the movie. I do think the movie does full justice to the book. Manoj Bajpai does such a good job with a very tricky character. So many things you mention in your review are things that also stood out to me. I was also struck by how the upheaval caused by partition changed social mores to the point that Urmila’s sister in law was accepted back in the family while Puro was turned away just a few years ago. Like you, this movie also made me question what love actually meant for Puro – she thought she loved her fiancé but that really wasn’t love. But did she really love Rashid, or was it just some form of Stockholm syndrome that turns into love in the absence of other options? I have spent so much time thinking about this story. It is exhausting but it is also very difficult to stop thinking about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And then you start to think, what is love? Not the falling in love part of it, but the every day comfortable kind of love. Isn’t a lot of it simply getting used to each other? The people that Puro and Rashid are at the end of the story are different from beginning because they have changed each other. The Puro at the end couldn’t be happy with a simple easy marriage to a man who would give her an easy life, and the Rashid at the end of the story wouldn’t be happy any more with a woman that he kidnapped and married out of pity, he wanted a wife that chose him. If Puro had married her fiance, she would be a different person and that different person could not love Rashid and could love her fiance. But she isn’t that person, the person she has grown into can only be happy with Rashid.

In its own twisted way, I find this a really good exploration of what marriage is. It’s not something that happens all at once because of a wedding ceremony (the way most films show it) but something that builds up over shared experiences and years together. Maybe Puro still doesn’t “love” Rashid in the typical romantic way, but she has fully become his wife and cannot imagine life without him.

On Fri, Apr 12, 2019 at 4:10 PM dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pinjar proves the adage that you can never really go back home.In Urmila’s absence, her family has moved on (except her brother).They have become different people shaped by different experiences and she’d never have found her place again.And even before that,she never truly knew her parents. Manoj was able to predict that Urmila’s parents would turn her away if she went back.Part of Priyanshu’s resentment with his wife was that he was coerced into marrying her.Him marrying Lajo was a condition for Urmila’s marriage.

LikeLike

Distance also gives perspective, right? Before, Urmila thought of her parents as wise and always right, and her brother as her closest friend. But now she has learned to live with different people and sees them differently. Her brother would still have burned the fields earlier, but Urmila wouldn’t have questioned it.

I missed that Priyanshu was coerced. Another connection between his marriage and Urmila’s. Priyanshu and Urmila were raised in an urban environment, reading newspapers and thinking about the issues of the day. Rashid and Lajjo were raised in a village with no world beyond that. But while Rashid and his family welcomed Urmila and helped her to accommodate to her new world, Priyanshu left Lajjo out of his world. We can see it in the two tattoo scenes. Rashid is forcing Urmila to have a tattoo, but in a strange way it is also trying to help her adjust to her new identity. Lajjo gets her name tattooed to hold on to her old identity, and Priyanshu doesn’t even seem to notice or care.

LikeLike

I don’t have any brilliant comments to make; but I enjoyed reading the review and everyone else’s comments. This was one of my first Hindi movies, and I almost didn’t make it through. I thought I knew how the plot would go–bad Manoj kidnaps Urmila and then her menfolk get her back–and the stagy, as you point out, acting and particularly Urmila’s keening sobs for half of the movie sort of put me off. And then I found myself crying my way through the last 45 minutes. I watched this for the first time around the same time I watched Bombay, so,yeah, that was a rough month.

This is my third rewatch and the best thing for me is the arc that all the characters go through–everyone gets some really really hard-won wisdom, and we see the positive and negative effects. Urmila gains the courage to save her sister in law, but she is never again the carefree girl running through the fields that Manoj fell in love with.

LikeLike

Or did Manoj fall in love with her? Maybe Manoj went through the same journey as Urmila, he had a fantasy of what love is based on someone he didn’t even really know (just as she had a fantasy about Sanjay). But as he lived with Urmila, the fantasy dropped away and he came to love the completely different person who was there with him.

On Mon, Apr 15, 2019 at 1:01 AM dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Yeah, I like that idea better.

LikeLike