This will be a fun post to write! A combination of audience, text, and industrial analysis, because all of those things combine to influence what happens to film. Part of what makes popular culture studies so fascinating to me! It’s the intersection of so many things.

Audience

2017 was a year of uproar, of change, of division worldwide. In India, the rise of the religious radicals lead to an increasingly bifurcated country. More importantly, the slow take over of public culture by the voices of the religious extremists made it harder and harder to find a source you could trust, a source you believed. And therefore, there was a rise in the power of word of mouth.

The message of the religious radicals is that no one can be trusted but them. Not books, not newspapers, not even your own judgement. And so concepts like “history” and “fact” and “common sense” begin to lose all meaning. In America, this has lead to the rise of Facebook messages and twitter as a source of “news”, everyone has an opinion but no one understands the difference between opinion and fact. In India and other places, it is Whatsapp groups that have taken this place. As the traditional media is overrun by radicals and distrusted, you turn to forwards from massive groups you belong to, and trust them unquestioningly because they are from someone you “know” (sort of) rather than the authorities you have been trained to distrust. Historians are corrupt and Western, news sources are false and prejudiced, only your hairdresser’s cousin’s wife’s sister has the “real” story.

What does this mean in terms of film, Indian film in particular? Well, first, the “traditional” sources of film news in India have always been untrustworthy. There are a handful of reviewers who make a sincere attempt to present an unbiased educated opinion on films, but they are drowned out by the voices of the ones who present a summary of the plot in 4 paragraphs, and a series of stars. And this has always been the case, the newspaper reviews of Indian film are not a very serious source of information or discussion. I am talking about 1940s through to 1990s here, not just the past few years.

With the rise of the internet and new kinds of media, streaming and DVD along with satellite, Indian film began to slowly reach new audiences and be talked about in a slightly new way. Film reviewing evolved, and there now are a handful of excellent reviewers working in the field of film. Popular reviewers, not just academic, but approachable by anyone and providing useful content beyond a summary and stars. But they have barely begun on the work of changing the way film is discussed and approached for the broad majority of readers.

So it is not that today’s distrust for media has moved readers away from these traditional sources, not the way it would be true in other places where every local paper had a dedicated reviewer who carefully presented discussion and analysis followed by a recommendation, it’s more that it has carved out a new space. Or shoved the growing legitimate sources out of the place where they have begun to have a foothold.

In “olden times” before film reviews, you had no choice but to go to the theater and take your chances. The same was true with watching a TV show, or listening to a new song on the radio, any form of media, the media itself generally reached you before the review. Or, sometimes, long after the review had been read and forgotten. Just looking at films, until the 1970s everywhere in the world, the norm was that a film would release in the major movie palaces of major cities, be reviewed by serious reviewers in those locations, and then months later reach the small movie theater in the smaller towns. Perhaps your family had a subscription to the big city newspaper, read the review when it first appeared months earlier. Perhaps you were serious about film and had cut out that review, made a mental note to watch the film when it reached your town, and now you are excited about it. But for the vast majority, either they never saw the big city newspaper in the first place, or the read the review and now, months later, barely remember it. You go to the movie based on the posters in front of the theater, on the trailer, or just because you feel like going to a movie that night.

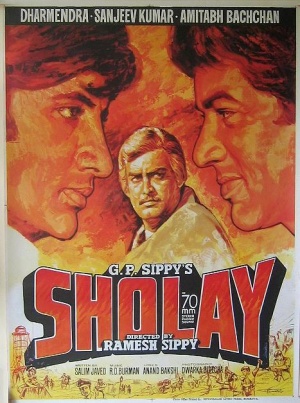

(Sholay had a great poster)

This began to change with the arrival of wide release films in the 1970s. Now your small town theater would get the film the same weekend as the big city, you would read the big city review and be able to watch the movie right away. But of course, not everyone got the big city paper still, not everyone paid attention to the reviews. And other people were still in the habit of simply going to a movie because it was a movie. And so films became a combination of word of mouth and reviews.

But Indian film skipped that era. Wide release is just arriving in India now, at the same time that the first generation of serious reviewers is trying to establish themselves. There never was an era of the small town getting the big city reviews and adjusting to the idea of some films being more exciting than others, while most people just went to the movies because they were the movies. Instead, there has been this sudden leap from “we just go to the movies because they are there” to “we are supposed to pick and choose our films”. But the problem is, there is no clear system set up to help pick and choose those films. The reviewers are there, but they are not trusted, they are a new thing and it is still hard to pick the wheat from the chaff among them. And now the public is being told and believing that no one can be trusted anyway, no one except the religious authorities teaching them what to think.

India has a long history of distrusting certain authorities, which is legitimate. The British freely invented “facts” in order to justify their rule, and only be digging deep and finding the real facts could the Indians break free. But the problem is, they are now still trusting their “authorities” blindly without realizing that these are the new authorities who now need to be questioned. A politician talking about history, is not as trustworthy as a historian talking about history. And a historian who is supported by the government is not as trustworthy as an independent one, perhaps even a non-Indian one. And the same is true in all fields. A little bit of distrust is healthy, but only if it is applied equally to all.

Anupama Chopra, let’s take her. She is not always correct in her reviews, sometimes she is infuriatingly incorrect. Her most recent little mini-post for instance, is essentially worthless, based on the premise that Salman Khan has never re-invented himself, which is patently false. Not “false” as a matter of opinion, but just plain not true. So Anupama should be doubted.

(She has great make-up though. Invisible, but just makes you think “wow what a pretty woman!”)

But just a little bit. Because her post on Salman Khan’s career is idiotic, does not mean that all her reviews should be dismissed, that we should never listen to her. And most of all, it does not mean that her opposite number is totally trustworthy. Professional film reviewer Anupama Chopra being wrong, does not make average citizen film protester, or even your aunt’s cousin’s friend who saw the film, right. The two do not balance each other.

That is what the Indian film audience is struggling with. Do you choose to follow the reviewers, most of whom are untrained and useless, and the few remaining are not consistently correct, or do you choose to follow obscure word of mouth paths from strangers? Or do you simply choose to always pick the one who says the worst, to believe the worst in all cases as it is seemingly safer than believing the best? And in 2017, believing the worst was the rule of the day.

Text

Strangely, while fewer people are watching movies, 2017 had one of the best years for films in ages. There were a number of films which crossed the line between art and mainstream, Angry Indian Goddesses, Lipstick Under My Burkha, Newton. In the solidly mainstream side of things, there were similar experiments and triumphs. Bareilly Ki Barfi, of course. Shubh Mangal Saavdhan also, the two of them point towards a new future for the rom-com in Hindi film. And, in what little I know of it, similar movements were happening in non-Hindi film. In Telugu, Arjun Reddy, Fidaa, Ninnu Kori, all had successful runs by focusing on small real stories, breaking boundaries. Malayalam film continues its new wave run of interesting magical realism/realistic type films. Tamil films continued their move towards that direction, 2017 seemed to be slightly more pulled towards the thoughtful relationship and social issues based films rather than the big blockbusters with stars. Kaatru Veliyidai did better than VIP2. There was also a rise of solid masala type crowdpleasers. Mubarakan, Golmaal Again, Judwaa 2 and I suspect similar light happy silly films in other languages also did well.

(Golmaal Again was also a sequel, which I will criticize in the next section, but it can both be bad because it is a sequel and good because it is light and happy and an ensemble, both things can be true)

And finally, of course, there is Bahubali 2. Which is a bit of a stand out. Similar to Sholay or Mughal-E-Azam simply in that it cannot be imitated. You cannot say that Bahubali will start a new era of content for film, because there is simply no way to match its content. It is one of a kind. What you can match are elements from it, the idea of a cross-language release, a leap forward in special effects and how they are integrated into a story, the artists behind it who are all being offered new opportunities. Bahubali, as a project for artistic scavengers, opens up a multitude of possibilities and options. We will not have another Bahubali in 2018, or probably ever, but we will have a massive influx of new artistic blood and inspiration into all the film industries of India following it.

There is a natural disconnect between audience and text in film, simply because of the delay between response and filming completion. This delay is getting longer and longer in Indian film as films get bigger and bigger (which I will get into in my industrial section), but there is always at least a 6 month gap built in. And so the audience was disgusted with films in 2017. The avoided the high quality products being offered them. Finally, by the end of the year, they were beginning to be willing to take a risk. But of course, this is too late. 2018 has already lost it’s start, the promise of Bareilly Ki Barfi, of the other small smart films of 2017, has been killed. If you look at the opening months of 2018, it is a series of unimaginative “safe” movies, mostly horror films and thrillers. The only films which the audience is still willing to try. There are no more small gems coming out, not if the audience didn’t respond to them 9 months ago when they first hit theaters.

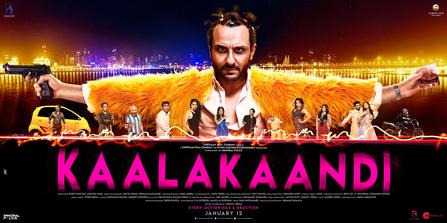

(Kaalakaandi is not getting an international release, because no one went to see A Gentleman or Chef)

And at the same time, the “Baahubali” affect is delayed. Saaho, the first major film from a Bahubali artist, will not be coming out for months and months still. Rajamouli’s next isn’t even in production yet. The Arjun Reddy effect is delayed too, the small human dramas that ruled the Telugu box office will not have imitators released for months, we are still crawling through more and more big star films that consistently fail.

Let’s talk about that big star film! These were the consistent losers, creatively and commercially, in 2017. Heck, they were the losers in 2016 too! There hasn’t been a straight up star film big hit in Hindi at least since Bajrangi Bhaijaan in 2015. I am defining “star film” as one built primarily around the persona of its lead actor, promoted on his name being in it, and so on and so forth. Aamir Khan of course had a hit with Dangal. But that was carefully promoted based on the story and his co-stars as much as on Aamir himself. Compared with, say, Raees which was promoted purely on the Shahrukh Khan name, how this was a different kind of Shahrukh Khan role, and so on and so forth.

And Bajrangi Bhaijaan, while it may have been initially promoted on Salman Khan, it was a hit because it was a lot more than Salman, it had a plot and a great actress costarring, even the songs were good. People took care with that movie, they worked hard on it, Salman on down, and they made something original.

But in 2017, there was no originality in the star films. The biggest hit in Hindi was a sequel, Tiger Zinda Hai. Heck, Judwaa 2 was a sequel too! Jab Harry Met Sejal was original, but felt like it had to hide it’s originality behind a title referring to previous hit films. The big star films were focused on doing what had worked before, but bigger. And it doesn’t work. It didn’t work in 2016 either, Sultan was a pitiful hit per screen compared to previous Salman films. There is a limit to this business minded way of making films, and we are at it.

(This movie somehow felt like something you had already seen before even while you were watching it for the first time. Which is fine for a regular Friday release, but no good for the one big film of the summer)

Industry

What first drew me to studying the Indian film industry was how human it was, compared to the American industry and most other film industries. Instead of learning about the government bureau of broadcasting or whoever funds movies in most countries, or about the massive faceless international corporations who run American film, I was learning about a network of families and friends and creative artistic partners who worked to create the best product they could just because they loved the work.

No one loves the work any more, that joy in it seems to have somehow drained out. It’s rare to hear producers or directors talking about how excited they are to make a film, how fun it was on set, how they just said “oh to heck with it” and tried something just for kicks. The lightness is gone.

This is why I love Rohit Shetty, by the way. Because he is still having fun. Films are fun for him, not business. There are other directors like that too, and actors, and composers and playback singers, I still get that sense of “can you believe they are paying me to do this?” But it is a lot less common than it used to be.

And what frustrates me so much is that they did this to themselves!!!!! The Hindi film industry has created a slow and calculated suicide, as sure as those women in Victorian times who used to poison themselves with arsenic in order to look paler. If you go back to interviews from as recently as the early 2000s, there is this constant obsession with being “professional”, “corporate”. A strong sense of self-hatred, that everyone in India is doing everything “wrong” and it is up to the film industry to pull together and force themselves to do things “right”.

What does “right” look like? It is the top 2% of society with purchased certificates showing they have completed a 6 month course overseas because it is easier to hire them than to figure out who is really talented and knowledgable. It is funding from overseas until your whole studio has been sold to westerners. It is crushing creativity where ever you find it, crushing originality, unless it is originality that looks like something else that you have already been told is original. It is creating an industry run by executives instead of creatives. With dozens of supervisors and no workers. An industry that serves the people who work in it, and no one else.

You know all the anger over Indian textiles, for instance, being made at huge factories instead of by traditional artisans in their villages? The same thing is happening to film, only instead of creating cheaper low quality products, it is creating more expensive low quality products. The traditional film artisans are being driven out in preference to young wealthy types with graduate certificates, the traditional film products with all their eccentricities and oddities are being replaced by brushed and perfect and boring mass produced products. And the traditional film audience is being driven away, to satellite TV and soon to streaming, as they can no longer afford the increasingly high priced tickets.

(I just started Rajnikanth’s biography. You know he didn’t even go to college? Forget that he went on to become a major star, he went on to become a brilliant brilliant actor. By learning on the job. Just like all the brilliant directors, actors, costume designers, everyone else in the history of Indian film did. Until today, when suddenly nothing matters but that 6 month training course you did abroad)

Corporate executives like things to be simple. They want to put money in and get money out. And so they put more and more money into star films in order to get more and more money out. They don’t like the idea of funding multiple small films and waiting for one to do well and one to do poorly.

This is where corporations failed when they first tried to move in back in the early 2000s. Chandni Chowk to China, huge amounts of money spent on what was supposed to be a “guaranteed” formula, a big star with big songs and big action. But back then, the audience was a little smarter and distributors and theater owners were too. It didn’t get a massive release, not on the scale that films are released now. Distributors didn’t get as fully behind it. Theater owners were careful. There was only so far it could be artificially driven up in box office.

Most importantly, there was a bigger and better audience back then. Instead of the majority of profits coming from multiplexes and just a few people at the top of society, they were still more evenly distributed through out society. And the lower levels were (and are) less susceptible to advertising and other manipulations because they just aren’t around them as much, less likely to see a TV ad and so on.

But now, the audience is a bunch of stupid rich people. Who think anything that is “Western” is good. Who are more likely to see a movie because of an interview they see with the actor who speaks good English and dresses like them, than because they like the poster or are excited for the film. And so the corporate practices are beginning to work.

A massive wide release, a massive PR campaign, it can drive in people to see the film against their will. But it also costs just huge amounts of money. The profits are disappearing towards a vanishing point. But it works well for a corporation, you can support your PR wing with your little overseas educated workers, you can support your huge executive branch of people sitting in on meetings and giving opinions, and you can keep sucking money from the overseas backers without them realizing that it is being spent on, essentially, nothing.

And so, from all the failures of 2017, the corporate studios are choosing to look at the one success: Tiger Zinda Hai. The budgets are going up and up for up coming films, not down. Bigger is still the name of the day.

I’ll put it this way. A big film is like a cruise ship. The captain and the crew are the ones doing the actual work, but there is tons of space for passengers, for the executive types who are just along for the ride. More space for passengers than for crew. A small film is like a yacht. The captain and the crew are the ones doing the work, and there is space for half as many passengers as there are for people to run the thing. Greenlight a 20 small films, and you only need 50 executives and 200 creative workers. Greenlight 3 big films, and you need 500 executives and 200 creative workers.

(Cruise ship! And a film that follows my theories, the Akhtars are really good at sucking money from big corporations for their little narrow-casting films)

And so we have 2017. The audience is struggling to figure out who to trust, how to navigate a new world of options, and is (so far) choosing to trust nothing.

The films are getting better and better, but no one is watching them.

And the industry is getting bigger and bigger in order to carry more and more deadweight along with it.

So, here are my hopes for 2018:

The audience learns to just watch movies again and make up their own minds.

The films survive on starvation rations until the audiences come back and then this creativity continues.

The corporate studios continue to slowly go bankrupt until eventually they all leave the country and the industry is owned by the people who work in it again.

I’ve been reading Anupama Chopra back from her India Today days in the 90s.Filmfare and sundry film magazines were considered ‘silly’ in our household and she was my trusted source to Bollywood.She’s someone I’ve grown up with and whom I trust.So naturally I’m prepared to ‘trust’ her.But to be fair to her, Salman had done little experimentation since ‘Wanted’.Bajrangi Bhaijaan was specially tailored to make him look good just as the final hearing on his case was being heard.There was a purpose behind it.To be fair to him, his films are still making money,his fans are happy.Why should he change just for the sake of changing?

As for Bollywood movies alienating their core audience to pander to the taste of the ‘rich elite multiplex crowd’ it is true to an extent.Movies like Dil Dhadakne do,Break ke baad,Kaopor and Sons feel more ‘Hollywoodish’ in their atmosphere and treatment.But Hindi films have always been about escapism and fantasy for the common man.So long as we have enough Bareilly ki Barfis, Newtons and Shubh mangal savadhans to balance them,it shouldn’t be a problem.There’s space for both.After all the parallel films of the 80s had a successful run along with the traditional masala movies.That said I expect realism from Malayalam movies,romance and escapism from Hindi movies and ‘something different’ from Hollywood movies.It sure makes me confused when the industries play with my expectations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think what is feeling upside down to me is that the films tailored for the majority of the audience, like Bareilly Ki Barfi, are getting the smaller release. While the films tailored for the top elite crowd are getting more promotion and bigger releases. I suppose there is a sense of “the single-screens will always be with us”, so no need to work in order to appeal to that audience. But it is odd, because looking at the industry from the outside, it would appear that the vast majority of the films are now aimed at the multiplex, just because those are the ones getting the bigger promotional push.

Also, I hate Break Ke Baad. I have only watched it once, maybe I will find the characters less horrible if I went back to it now, but probably not. Stop whining about your horrible life as a spoiled rich kid with an awesome boyfriend/girlfriend!!!!!

On Mon, Jan 15, 2018 at 8:08 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

The problem is that the current generation of Bollywood actors and technicians have no idea about the life of a common man. They have been educated abroad.Naturally they make the movies which appeal to them. They wouldn’t get Bareilly or Newton.Their parents,the yesteryear stars- for all that some of them have been starkids- essentially grew up in India.Sure,they were rich and privileged.But they had enough background information to play different characters appealing to all sections of the audience.Sure, as Ratna Pathak said a lot of the 70s village belles were running around with perfectly groomed eyebrows,but they knew enough stuff to be convincing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is what I was getting at with the problems with the industry. It’s not just actors, if anything they are the most connected still. Even if they were raised in international enclaves, at least the majority of their training is still on set. But the writers and directors and costume designers and everybody are now supposed to be “professional”. Meaning they received all their training abroad. The dressman, the spot boys, the cameraman, the writers who were trained on set within the industry are now considered “old-fashioned” “unprofessional”. If you look at the behind the scenes staff at Dharma or Yash Raj, all those interviews that pop up on Anupama’s channel and so on, everyone is very proud of how seriously they take things and how professional they are. But no one speaks Hindi or seems like they would have any kind of an idea of what a lowerclass heroine would actually wear, how she would talk, do her hair. It used to be that the rest of the staff on set was lowerclass workers from Bombay, they added that touch to the films and kept the directors and actors grounded. Now everyone but the very lowest level is these highly educated rich kids, and they don’t really interact with the spotboys and so on. So no one knows their audience any more.

Or, more accurately, how a lowerclass audience member would dream about an upperclass heroine looking. Asmita I think asked me last Monday if I thought Hindi films accurately represented society. It’s not that I want them to actually reflect society, but I want them to reflect the dreams of society. the heroine’s ridiculous poofy satin gowns in the 90s, that felt like the kind of thing a regular person would dream of owning, you know? Whereas the Western-chic style the heroines wear now, while probably more accurate to what a “rich girl” wears, is less of a fantasy.

On Mon, Jan 15, 2018 at 10:25 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

You named Anupama, but I want to ask you if there are Indian critics you would recommend. Generally I only read critics after having watched the movie because I decide according to my own interest triggered by whatever.

I think, multiplexes and ticket prices have done a lot to diminish the number of people who ‘just go to the movies’, so the influence of random critics and social media verdicts has increased. When I read what people have to pay for a Padmaavat ticket, it is clear that a big part of the population is excluded…it is a way to destroy the Indian movie culture (I ask myself if there even exist the travelling cinema).

Text: I hope the masala will remain…with ensemble starcast…and also the star cinema…there is room for everything, it would only be more and more a matter of ‘less may be more’. If, f.ex., the story of ShahRukh’s new movie is dense and gripping, the concentration of an excellently made VFX-work will be seen as another well-made ingredient (and not the main purpose).

Industry: I would like to know what you think about RedChilliesEntertainment.

LikeLike

I like Raja Sen and generally the rediff reviews are my go to. Anna Vetticad and Bhardwaj Rangan are also good, but tend to focus more on non-Hindi. And they all do their job of attempting to give you a sense of the film beyond a simple thumbs up or thumbs down. But of course they are lost in the sea of other opinions. I used to read every review of every movie, but since I started blogging, I am worried about simply repeating their words so I don’t any more.

I like your point about the VFX work versus the text. I felt like Ra.One and Fan worked as movies beyond the special effects, but I could also see how for some people the special effects would overshadow the rest of the film. Hopefully there is a better balance with Zero. And if there isn’t, I really hope that Shahrukh starts using the VFX in movies he produces for other people (I am sure he is working on Brahmastra with Karan), and keeps his own moves slightly smaller and more based on story and star.

RedChillies is interesting. I wish they would produce more. They seem to be one of the better middle-man production houses, they will take a good idea and script someone else has developed and provide the funding and publicity. They stumble when producing entirely on their own (Asoka, Phir Bhi, Ra.One, etc. etc.), but when in partnership with another strong creative hand (Main Hoon Na, Dear Zindagi, Ittefaq), they do very well. I suspect Shahrukh has a good eye for a script and a director and he is increasingly learning to trust his instinct on the films Red Chillies produces, but is still choosing wrong when it comes to the films he stars in.

On Fri, Jan 26, 2018 at 10:02 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike