Last section! Bringing us through to the present day (finally) and the situation now as movie theaters close their doors and the internet struggles to replace them.

Usual Disclaimer: This is all my original thoughts based on publicly available information.

When you introduce a new product, the biggest challenge is convincing people they actually need it. After all, they have gotten along without it up until now, why should they change?

The visible part of this process is the ad campaigns. And for many products, that is all there is to it, psychological tricks to convince us we cannot live without something that we lived without up until now. Deodorant, for instance, a product that did not exist 100 years ago and today we all assume we cannot live without it.

There are also the products that we do sincerely need. Antibiotics, when they were first discovered, there was a bit of a climb to convince the public but it wasn’t that hard. Because they filled an actual gap, before them people died, and after they didn’t. Even the telephone could be added to this category, before it there was no way to quickly call for help in an emergency, or have an important conversation across great distances.

But then there are the vast majority of products that we use every day only because the producers created the need for them. Not an imagined need on our part, an actual one, but one that only exists because the product that used to fulfill was killed in order to make space for this new one. An obvious example is the car and the streetcar. General Motors bought up streetcar and other transit companies all over America, and then closed them down. People HAD to buy cars, because the only other easy transit option had ceased to exist.

(Streetcars piled up and left to rot)

The story of a new product is usually a combination of these 3 elements, the imagined need created by advertising, the actual need that lead to the original development of the product, and the actual need resulting from the murder of the previous product that fulfilled it. And if you look back at all we have talked about in this series, you can see how, depending on the era, this is also the story of media development.

Let’s go back to radio for a moment. When Radio was first launched, most of the world was rural. Houses separated from each other, families with minimal interaction with the outside world. Radio filled a need, you could bring it home and then there were no wires, no need to be closer than a few dozen miles to the radio tower, and you had a connection to the world, an entertainment center, something to stop you from going just a little bit crazy (mental illness was an actual danger and concern on some of those more remote farms, especially for the women trapped inside).

But the need for profit is vast and radio manufacturers couldn’t be satisfied with just those users who truly had no other option. And so ad campaigns started, telling you that you HAD to have a radio, even if you didn’t think you did. And more than that, slowly, radio edged out what had existed before. Going back to those farms, during the winter or on the more remote farms, radio was a necessity. But in the summer, or the places closer to town, women would go visiting, there would be massive gatherings on a regular basis, families would go into town, often would have a second house in town for the winter, or even just to have the women and children live there year round, let them enjoy human contact. Radio was a poor substitute for this, for actual interaction with others. And yet once radio arrived, those other options became less and less. Even more with the introduction of TV. Suddenly the idea of a winter house in town, or of driving an hour down the road to spend the day at the closest house, became less and less acceptable. You had your artificial imaginary friends now, why would you need your real ones?

(Have you read this book? The most “adult” of the Little House Books? There are SO MANY crazy farm women in it!!!!! Women who just couldn’t take the isolation and slowly went a little bit insane)

This is the same change that came with the arrival of satellite TV in India. Women who previously would sit outside during the day, go on family outings in the evenings, all sorts of things that were known to be just necessities to keep them sane, are now left inside with the substitute of the television for human companionship. Again, a necessity, something that makes the day go by much faster when you must be inside. But also creating its own necessity, the previous ways to pass the day are now unavailable as TV has been forced to replace all of them.

And now we have the internet. I’m going to ignore the way it killed newspapers, physical letters, phone calls, and real world socializing. Let’s just look at entertainment, specifically movies and TV.

Netflix and Amazon Prime have slowed their market growth in America, and so they have turned their eyes on India, the largest and fastest growing internet market in the world. This battle between them has been waging for years now, and film is a large part of it. Most movies now come out with a front piece stating “exclusive Amazon” or “exclusive Netflix” right there while it is in theaters. Shahrukh signed an exclusive deal with Netflix for every product from his studio or owned by his studio.

It’s not just Netflix and Amazon Prime. There is also Hotstar, which began as the streaming portal for the Star India (subsidiary of Fox) TV shows, but also makes available the massive film library acquired by Star for their channels. And Hotstar has quality managed a true exclusivity for almost everything they offer. If it is on Hotstar, it is not ANYWHERE else. DVD, one time streaming purchase, nowhere but Hotstar. I suspect because they acquired rights through satellite sales, not through streaming, which gives them a much higher degree of exclusivity.

Similar to Hotstar is “Voop” TV, the streaming branch of Viacom18, the Indian version of Viacom (the worlds’ largest entertainment conglomerate, they own essentially everything). Again, it is taking the massive library already owned by the TV channels and providing them through a new format. And SonyLIV, structured to do the same for the Sony TV channels and content.’

And there is YuppTV, which has no parent TV company but instead combines multiple channels into one platform, allowing the streaming of live TV along with a video library. Based in Hyderabad and Atlanta, it has always been more focused on the overseas market, and the south Indian market (it recently acquired HeroTalkies, one of the main streaming sources for Tamil/Telugu films).

Not even big enough to make the graph is the newest entrant, AltBalaji, launched just one year ago and a subsidiary of Balaji telefilms. A straight production house that has never been involved in distribution before. And their focus is production, they create new top level TV shows that are only available on this platform. It’s not a massive streaming library, instead it is focused purely on the very best original content in the serialized format available anywhere.

Amazon hit the Indian market before Netflix, in the old-fashioned form as a website offering online ordering. And they were obviously able to leverage that, along with the interest in international streaming options and purchasing the ErosNow library, into taking over the Indian market. And they then went on to offer their own Indian original content through limited series. And now Netflix is trying to compete by providing high quality original content. Only it has to be bigger and better content. While Amazon Prime offered Breathe featuring Madhavan, a major movie star, and Amit Sadh, a barely known movie star, and a variety of talented character actors, Netflix offers Sacred Games with two movie star leads, surrounded by other well known actors, and two superstar directors, and a massive budget for sets. It is lush and visual and expensive. And it worked, based on my blog stats, the audience is turning out and tuning in for this big showy adventure.

If I am looking at that closed graph of the streaming market and thinking about how those colors might change, I see ALTBalaji as the biggest threat to Netflix. Because it offers content of a similar quality (stars like Rajkummar Raro in their series, maticulous recreation of historical periods), but it is all Indian content, and all original exclusive content. And it is a familiar trusted brand name. I also don’t see Hotstar losing it’s death grip on the market any time soon, thanks to the massive exclusive library of Indian content that cannot be rivaled by any other company. All Indian content too, Hotstar has films and shows in every language of the country, while Netflix and Amazon are still more limited to just Hindi.

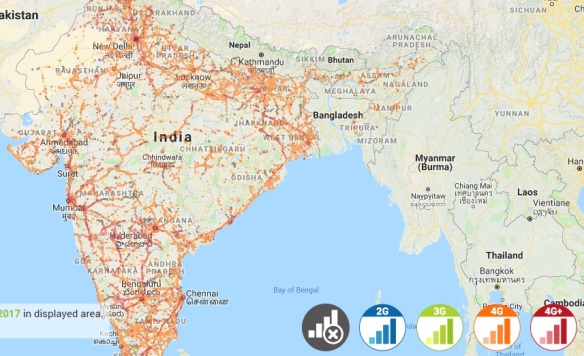

But here’s the problem. The world isn’t reflected in that graph. In India, 64% of the population has no internet access at all. And half of those who do, do not access the internet on a daily basis, indicating they have either uneven service or must use a public access point. And yes, this DOES include cell phone coverage, not just wired.

Reliance Jio is the only cell phone company that comes close to covering the whole country. And they have massive gaps in their coverage, especially in the central rural areas of the country.

Here’s another image showing the breakdown of internet access across demographics in India. College students and men, young and old, are the majority.

And of course the majority of college students are also male. Lower level degree programs have had an increasing number of female students for years, it is almost 50-50. But the higher degrees, graduate and Masters and PhD, continue to tilt male. And India lags behind the world in working women as well, at least educated working women. If we look at this graph with that in mind and picture an urban area, what we are seeing is young men and women in high school and undergraduate programs with easy internet access. That access continuing for young men as they graduate and for the majority of women who graduate into lives as housewives in middle class urban households. But for working women (most likely domestic labor rather than office), there is no access. Even the women with the luxury of not working have less access than they had in school. The internet is available, certainly, if you are a student, a man, or working in an office job. But not for others, not even in urban areas. 78% of urban dwellers have internet access, and those left behind, the remaining 22%, are most likely female, or poor.

That’s in urban areas. 70% of the Indian population is rural. And only 23% of them have internet access. ANY internet access, these studies did not measure for speed. Or for level of access. There is a government push to provide public computers in community centers in rural areas, and there is already a popular habit of internet cafes. That will work to do research for school papers, or check for email or Skype with relatives. But it will not provide the ability to access streaming content, to settle in and watch all 7 hours of Sacred Games on Netflix.

None of this is necessarily a bad thing. The internet market is growing steadily in India, the infrastructure is being built, things are shifting naturally. Star TV to Hotstar, Viacom to Voot, a reasonable change, the same content that is popular on the now well-established TV market being offered through a different platform. ALTBalaji, good, a new way to offer what is called “parallel” content, not quite artsy but a little more intellectual and high quality than what is popular with the mainstream. Let the streaming services battle for the market of internet users, let cell phone manufacturers and service providers battle it out for the market of new internet users, let everything keep happening as it does.

The problem is, going back aaaaaaaaaallllllllllllllllllllllllll the way to the start of this post, the new internet companies aren’t just trying to manipulate the market, they are creating the market. Maybe not even intentionally.

If Netflix wants to make Sacred Games, and other content of a similar quality, that means it is competing with the movie industry for both resources and audience. If Saif and Nawazuddin are spending the next 4 years filming Sacred Games, it means they aren’t making as many movies as they could be. And neither are the directors Anurag Kashyap and Vikram Motwande.

At the very top level, all Indian film industries (Hindi, Telugu, Tamil, Bengali, everything) have exceedingly limited resources. There are only a few top stars, directors, and music directors. If one of them is taken away from the mix, it is a loss that is immediately felt. And now the film industry is suddenly competing with streaming companies for those scarce resources. They aren’t just buying products which already were in theaters, already helped support the film industry through ticket sales and traditional markets, they are rivaling the industry by making their own products using the same limited resources.

And it is competing for audience. The high paying audience, the leading audience, the “taste makers” who publish the reviews and participate in internet message boards, they are leaving film for streaming services as well. And encouraging the rest of the country to follow them, stop watching the boring old fashioned movies and switch to streaming instead.

Except, they aren’t actually encouraging the “rest of the country” to follow them. They are encouraging 36% of the country. The remaining 64% doesn’t know they exist, doesn’t know about internet message boards and streaming sites and all the rest of this, because they aren’t online.

And this is the problem with streaming in India. It only sees a 3rd of the country as even existing. And yet, it is taking away the content from the whole country. In 2013, there were twice as many theater admissions sold than the entire population of the country. Meaning everyone in India went to the movies at least twice, most of them 3 times. EVERYONE. Not just 1/3rd.

India is still underscreened, far fewer movie theaters than there is population. But if you add in the uncounted traveling theaters, allow for the low ticket prices, and consider who it is that is still lagging behind in the internet stakes, you can see that the gap left by internet coverage overlaps with where film can fill in. The urban working class woman and her family can afford the cheap ticket prices at the urban single screen theater. The rural farmer can take his family to the tent theater a few times a year. You don’t have to pay a subscription price, you don’t have to have an infrastructure to build it, you just need enough electricity to run a projector for 3 hours (or a generator) and a few rupees for the ticket. Or at least, they could. Now those theaters are closing down and disappearing, and being replaced by satellite television, DVD parlors, and the internet. Or, for a large number of their audience, nothing at all.

This is the problem with the big international companies. Hotstar and Voop, they are providing content to match their TV offerings, not trying to claim new territory. ALTBalaji is neatly and carefully filling the small gap left, high quality programming and nothing else. But Netflix and Amazon are ultimately creating a gap they cannot possibly fill, not yet. If they succeed in driving highpaying viewers from film to streaming, and driving artists, then the film industry will become a ghost town. And nothing will be left for that 64% of the country who have no internet access at all.

But then, do the international corporations even know about that part of the country? Do most people, that is, most people in the internet-having class? The internet is so all encompassing now that if you are not on it, you are literally invisible to those who are. That 36% of the country probably thinks of itself as the entire country, entertainment only discussed as they discuss it. We see this constantly in the radical difference between the accepted wisdom of a film’s popularity and the reality. According to the internet, “everyone” hates Dilwale despite it doing an excellent business at the box office? And “everyone” loves Gangs of Wasseypur despite it barely getting a theatrical release? At least with film, there is the raw box office data available to counteract the accepted narrative and prove that this 64% DOES exist. But streaming doesn’t allow for that, the data is already limited to only the 36%, any discussion excludes the 64%, makes it as though their needs don’t exist, their desires don’t exist, their tastes don’t exist, they don’t exist.

Mass media began with the hope of bring these geographically and demographically massive countries, America and India, into one community. And they have succeeded in breaking down geographic boundaries, only to create new ones of class, of age, of gender. And in India at least, there is now a boundary so massive as to trick the eye into believing there is nothing on the other side of it, into believing that you and the people like you are the only ones, that “everyone” has internet now. You hear this all the time, don’t you? “Everyone I know is online”. And that’s true, and that’s the problem. Everyone you know is online.

The US had a huge divide between rural and urban internet access until very recently. Much bigger than exists currently and I suspect the gap will continue to narrow. Do you think a similar thing will happen with India? Is the will there to invest in cell phone access at least? If rural areas lose access to films could that create pressure to extend internet access to the rest of the country?

LikeLike

I think it is already happening, the number of internet users in India is exploding thanks to 4G cell coverage. But the problem is, the perception is speeding ahead of the reality, so much is happening online now, years before the whole country will be online.

As of 2016, 16% of the country still doesn’t have electricity, let alone internet. The unwired internet has seemingly avoided the infrastructure requirements, but you do still need electricity somehow. And literacy would help, 26% of the country are still illiterate. And only 12.6% speak English, let alone read English, making vast areas of the internet unavailable to them even if they were able to access it. Not that English is the most important thing in the world, but it’s a big part of being able to interact online. Think about all the comments and excitement and so on on the Indian English language websites, all of that only represents 12.6% of the population.

I doubt that the loss of film will make a big difference, the urge to reach the total population always seemed to be something that film stars cared about more than anyone else. Thus Ajay and Salman buying up and opening their own single screens in unserved areas. When I was researching this I ran across an article from Forbes talking about the Indian film industry and focused on the goal of more multiplexes and higher tickets, because why should you keep tickets low? Which I assume is the attitude of the bean counter types, why worry about serving rural populations? They don’t have any money!

Satellite TV is the most likely fill in, you don’t have to be literate to enjoy that. Especially because I’ve noticed the popular Indian TV shows are barely talked about online, which makes me think they must be watched by the people who can’t get online.

On Thu, Jul 19, 2018 at 7:48 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

The popular broadcast shows aren’t talked about online either. Isn’t Big Bang Theory the most watched show right now? And not a peep about it online that I can tell, unless it’s on sites I don’t visit.

Something else I just read that fascinates me: in the US 20% of the population could get internet access (either through a cell phone or home internet) but they aren’t interested.

LikeLike

Now I am confused, is it that the 20% have internet and don’t use it (thus being counted towards the 87% overall), or that they have broadband or other services available and don’t want it? Or is it 20% of the 13% who don’t have it? Because that I can believe, I know loads of people who had to be dragged kicking and screaming into the internet and I can imagine a small percentage of folks who had no one to drag them just never giving in.

And yes! The Big Bang theory is never discussed online, or NCIS, or any of the other reliable ratings hits. Which kind of makes sense to me, because there is the divide between the vast majority who watch non-broadcast shows (as the ratings continue to creep further and further down), and the tiny minority that still do. Or else just that they are the kind of brainless fun entertainment that you can enjoy watching without thinking about 🙂 I watch them off and on myself, and somehow never really feel the urge to discuss them.

On Thu, Jul 19, 2018 at 8:45 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Here’s the article I’m referencing. It’s five years old so maybe out of date. https://www.theverge.com/2013/8/26/4660008/pew-study-finds-30-percent-americans-have-no-home-broadband

LikeLike

Thank you! That makes sense, I can easily see the rise of cheap smart phones and tablets closing half that gap in the past 5 years.

On Thu, Jul 19, 2018 at 11:41 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

I’m so used to seeing a production bubble as a windfall for producers – even if it doesn’t last, the money is good while it’s there – that I’m having trouble wrapping my head around the dilemma you’re talking about here. Not that I think you’re wrong, just that it’s different from how I’m used to thinking and what I’ve seen in the US and Europe.

Taking Sacred Games, I see Netflix following the same model they did for their recent hit Money Heist, which was also a crime drama. (I thought this was an original, but it turns out it was a series originally broadcast in Spain, but which Netflix got on exclusive and re-packaged for international release on the Netflix model, which turned it into their most watched international show to date.) Or Narcos, which is filmed in Colombia. There was a really interesting interview with Erik Barmack, the Netflix VP of International Originals, on Film Companion ahead of the Sacred Games release. He said they release their originals “all episodes at once, in 20 different languages, 190 countries.” That is a lot of languages, and a lot of countries! To me that means they’re making shows that they hope will be popular in their home countries, but their model is built on smaller audience share distributed widely across many different countries. If you look at the summary Netflix released of their most popular shows of 2017 (https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/netflix-most-watched-shows-2017/), a bunch of them are international, which is unusual for a US company.

The usual US model is you make shows or movies for your big home market, but which also have strong international appeal for audiences in other countries. But Hollywood is powerful and so are agents and unions and making shows in the US is expensive, especially for a new entrant. In lots of other places, there is a small film and TV industry, often starved for resources, trying to compete in its home market against an influx of content from outside. For those local industries, Netflix is a godsend, it rains money and opportunities on local talent and new creations come into existence that might never have seen the light of day otherwise.

India, as you point out, has a big local industry and already has expertise in reaching viewers in other countries and creating shows and movies for different kinds of audiences. In many ways, this makes it a perfect match for the kinds of shows Netflix is looking to create – probably why Barmack said they’re growing production faster in India than they have anywhere else, even faster than they had intended. That’s great for Netflix’s model, high quality talent and production houses at cheaper than US costs. It sounds like it is also offering opportunities for creators to make things they wouldn’t have otherwise gotten to try because they didn’t fit into the existing distribution models. And from what you wrote about access to streaming (of the legally sanctioned variety), Netflix productions would reach a relatively small percentage of the total Indian audience for films, so it’s probably not too big a disruption on the domestic distribution side. Netflix isn’t competing for the same audience as the single screen theaters. More the multiplexes? But it sounds like multiplex theatergoers are still much more numerous than streaming consumers. (And if producers make big money off of satellite rights sales, satellite customers are important too – not sure what the overlap looks like there.)

So it comes down to the dilemma you name, if there’s enough talent to keep feeding both the traditional domestic audiences and the new international channel. Maybe a bunch of second tier or younger actors finally get their big shot, with roles and scripts that would never have been made under the traditional model, and we finally get the answer to whether star kids are in all the movies because of talent or nepotism :). Maybe older actors get drawn out of retirement because there are interesting stories for them to tell. It’s possible the streaming content bubble would limit the attention available to be spent on domestic projects, but it’s also possible the production houses will have more cash to spend on new projects.

LikeLike

See, it’s that last that makes me nervous. Because in theory there are plenty of known actors in India to feed into Netflix, Prime, whatever. But that’s only if you look at it as one market instead of several. Madhavan in Breathe was a perfect actor for the Hindi market, familiar reassuring face but not quite big enough to headline a film. However, in Tamil, he is headlining and producing. But not this year, because instead he made Breathe. It’s that balance, finding a known actor who isn’t really too big to be wasting his time on Netflix that I am nervous will be messed up. Because it would be so tempting to steal them away from films, the money would be better and so would the artistic fulfillment most likely. But it wouldn’t be fair to the audience. And ultimately, it will lower your star power. Movie stars in India are kings, control governments and own the hearts and minds of the people. To lose that and be brought down to just small screen size would be a dangerous loss for the survival of the film industry.

ALT Balaji gets it, in their shows they have Sanjay Suri, Mandira Bedi, the biggest star is Rajkumar Rao. And they are breaking all the rules, a female Devdas, a series of rural sex stories, a same sex romance soap opera, and on and on. Perfect combination of boundary breaking without monopolizing mainstream talent.

Anyway, bottom line is that I come at things from a media studies perspective and am obsessed with thinking of the audience instead of the artist, so I don’t really care that much about the artists finding artistic fulfillment and money, if it means the audience is left unserved.

On Fri, Jul 20, 2018 at 12:33 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

I understand what you’re saying, because there’s a lot of overlap between actors and producers in the Indian industry. But if Madhavan got paid well for Breathe, that means he has more resources to make his next homemade project too, and potentially a wider fanbase that project could reach, which would make it more profitable. In the best case, it gives him access to additional resources and distribution channels to build his production side.

LikeLike

Oh you are just trying to cheer me up and i am determined to look on the dark side. Nothing is as good as it used to be and never will be again!

LikeLike

In this entire series you have overlooked the fact that indian content on streaming platforms is watched primarily by Indians. Because we’re everywhere. And in huge numbers too. And we miss home a lot.

Domestic TV audiences, well, we get both English and Hindi shows on TV plus films and on an average day, like the housewife plus mother in law, they just want to have their favourite series on while they’re catching up on their social media updates.

Series like Friends, Seinfeld and Frasier and The Office, all of these became popular because they were on your TV all the time. At least in India, the channels gave them so many reruns you basically grew up with a series that ended before you watched its first episode.

You put the TV on the first thing in the morning (news or music till dad left for work) and then your English shows till you had to leave for college or school. And then you got back and had the same shows on while you had lunch and did your homework or called up friends. And then your dad came back from work and it was his TV time which would be either the the news or a film or an educational program like KBC or if there was a cricket match on that’s what you’d have on all day.

This was when you had just one TV. Multiple TVs in the same house are not uncommon now because the bahu usually gets a TV in her dowry but since you bring home a bahu of your own choice, you mostly watch the same shows. And you have to lock yourself in your room to get a sense of isolation. Because there’s just so many people. Everywhere. Even in your own house. And socializing always takes precedence over entertainment. Rather, entertainment is a part of socializing which explains why movies, even really bad ones, get audiences.

LikeLike

The socializing part has a big big effect on what kind of content is provided. It’s something that I’ve noticed in the multiplex versus single screen switch in films. In the single screen films, you could feel the pauses for whistling, the moments when it slowed down after intermission to let people get back in the room, and so on. Like Dilwale, worked much better when I watched it opening night in a packed theater with whistles and cheers, than any other time I have watched it. And then something like Kapoor and Sons is this perfectly crafted thing that only works if you pay close attention in complete silence straight through.

And I assume the same is true for TV content, it is crafted to be something that the whole family can have on all the time, nothing super objectionable, nothing you really need to focus on to enjoy?

If that is the case, the streaming companies (besides Hotstar, which is just using the same stuff they are already broadcasting) are really going to struggle to figure out what content will get people off the TV. Because it has to be something you don’t really care about that much, but would still care about enough to switch formats.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 2:28 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Yup. It’s all pretty much at the same level of comfort as K3G and that genre of films. You can discuss the jewelry, the clothes, the family values, the familial conspiracies. It’s almost like an extention of what’s already happening in the average indian household. Only glammed up x1000

Streaming platforms in India started out focusing on the demographic that misses out the most on TV time- boys that watch foreign football leagues and those that can’t get to a TV (or get vetoed by women at home) to watch a cricket match. For a few years now, rights to cricket series and football league broadcasts have been bought by channels that aren’t part of the regular satellite package or come with prices and terms that make it look like a significant amount. Usually, you can just go to a friend’s house and watch the match if he has the channel. Or, you stream it on your phone and watch while sitting in the living room when your mom and sisters enjoy their soap.

Men and boys are the great untapped audience for TV series.

Of course, the most natural answer to the streaming question would be for these platforms to focus on getting more films. Both English and desi and also world cinema. Things you can’t even dream of watching on TV with your family but you want to watch it because it got recommended by a friend.

LikeLike

Well, that explains my Hotstar. I understood why the home page was filled with their soap operas and original serieses in multiple languages, I assume they are trying to gather more viewers for their proprietary content. But I had no idea why I had to scroll through sooooooooooooo much Cricket. And Kabaddi and IPL and blah blah blah. Makes sense if that is the content that is most likely to get them new viewers because it is hardest to get non-streaming.

If promoting films is the solution, than Hotstar has got to be more serious about making their current library accessible. They have so many rare film classics, but they are impossible to find, because they are frontloading their soap operas. If they took their library, made it searchable by star or audience rating, better yet broke it down by genre by language (Classic Malayalam, Action Tamil), you could easily spend days browsing through and discovering hidden gems. But instead everything is just thrown together in a useless pile.

It’s like a poorly designed shop. The old junk shop may have far better things than the fancy expensive antique store, but the antique store is clean and brightly lit and has it all neatly laid out on shelves, and the jump shop makes you dig for what you want. And in this case, Netflix is the antique shop. Comparatively much much fewer items, and none of them very rare. But all neatly laid out and easy to find with handy algorithms to suggest more like it.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 9:23 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Not to mention that they keep suggesting the same films over and over again!

LikeLike

YES!!! And they are terrible films! Netflix and Amazon do the same thing, trying to get their money’s worth out of a recent purchase, but at least it changes once a day or so. Even Friends was only promoted for a week. I am so sick of having Aadu 2 recommended for me in Malayalam.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 9:39 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Do we know that most people who watch Indian content internationally on streaming platforms are Indian? I can’t find any reliable audience data to speak of – Amazon is notoriously opaque about user data, and Netflix also seems to keep their audience data a closely guarded secret.

From everything I can read on Netflix’s strategy (for instance this 2016 deep dive from Wired https://www.wired.com/2016/03/netflixs-grand-maybe-crazy-plan-conquer-world/), it’s about finding ways to be less dependent on content from the powerful US industry, and building local catalog with an eye to international distribution. Which, given their Indian film catalog (at least what I can see of it from the US) vs. the distribution of their subscribers (out of 100 million subscribers worldwide, a little less than 50% in the US, and still very small numbers overall in India) says to me they’re looking for new audiences for that content beyond viewers that are already fans. This is where the biggest potential for marginal growth is. The big US shows and movies are a known quantity, there are well documented audience numbers from years of international distribution through traditional media. These are also the most expensive and competitive for Netflix to provide. Industries in other countries, on the other hand, have mostly not had such broad distribution, so there is unknown and mostly untapped potential in getting their content more widely distributed. Anecdotally, I’m hearing from a surprising number of people watching Korean shows on streaming platforms, for example.

The Wired article describes a way of slicing audience preferences and demand not by region or a broad brush demographic like ethnicity but by viewing behavior, regardless of where you live. This is also how they’ve talked about deciding which shows to greenlight, by seeing there is a strong demand across different countries for a certain kind of gritty, character driven crime drama – which they now seem to be trying out in different local settings (Narcos, Money Heist, Sacred Games.

LikeLike

That would also match with the distribution pattern of Indian film. From my research, long before the NRI market grew, Indian film was already doing well overseas. It translates very well, with all the non-verbal cues and universal human concerns.

The problem being, Indian film has always traveled well from subordinated people to subordinated people. Not so much wealthy to wealthy. So there is the possibility that the international market will be stuck with the same issues as in India, the people who would really really love the Indian content are the ones less likely to be online.

At least, the existing Indian content, the films like Kaho Na Pyar Hai or Chaahat or even Dangal. But your point, creating something like Sacred Games brings that Indian flavor in a format that is much more First World friendly. And there was already the data on, say, the Indian section of Sense8 getting good feedback, showing people are interested in that area of the world.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 11:56 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Yes, Korean and Turkish dramas got huge in India too. There was at least one south American soap on Zee in the 90s which was also very popular but somehow they didn’t get more of those.

It’s curious that there aren’t proper numbers for what demographic is streaming desi content overseas. But then again, that’d be close to profiling.

I’ve only anecdotal reports from friends living abroad and non desi friends that tell me that it is in fact desis that consume the most desi content. Sure there are the odd TV channels that cater to that but they don’t have all the desi shows. Or films. Plus, there’s always the crowds at indian film screenings and indian DVD stores to give one a fair overview of the demographic that might be streaming that same content on a regular basis.

LikeLike

Based on what I see at stores and theaters, it’s about 5% non-desi. Which is a very unscientific measurement.

However, what I found in my research for my thesis was long running semi-official distribution channels among the third world. Nigerian TV channels, Hmong dubbed VHS tapes available at Hmong grocery stores and so on. But that’s kind of invisible data, both because it is semi-legal and because it is another closed system, you would only know about those experiences if you were already going to Hmong grocery stores, there is no way for an outsider to notice it. Just like the Indian movie screenings are apparently invisible even when they are in mainstream theaters, tucked away on their own screens with hardly any publicity.

I was really interested that Prime apparently started out trying to recreate that, with their separate subchannel of Indian content, segregated from the rest of it.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 12:08 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

That’s still where the money is going to be made. Not in India. You gotta sell india to the Indians overseas! Look at what that did for SRK

LikeLike

I know, it would be much more fun to have good data to play with! This is the problem with these big tech platforms that jealously guard their user data (and no longer have to talk in public about audience to get ad buys). Usually the only way to get around their lockdown is if one of the content partners – a producer or a studio – says something in public about what they see for the audience for their films or shows and where it’s distributed, because they do get access to that information. But they’re also probably under some non-disclosure agreements. And even if one of them talks it gives just the small slice of what that one provider can see for the films or shows they control. We need an Indian media reporter to ask Reed Hastings this question :).

I’m seeing an Indian diaspora according to UN figures of 15-16 million. Which is big – I think the second in the world in terms of diaspora – but not that big if you’re a Netflix or Amazon trying to grow subscribers really fast, compared to either potential audience inside of India (I get it, severely limited at the moment by many different and hard to solve factors!) or potential non-desi audience worldwide. The NRI audience is also probably smart at getting its content through channels that are not Netflix or Amazon, some of which alternative channels (like Hotstar) may be sending money back to the producers and some of which may be unofficial, which is another factor that might limit how much growth you could get out of targeting that audience, because they already have their preferred channels of online content.

Totally agree about the makeup of movie theater audiences, I’m just not sure that will look the same as the streaming audience once online distribution grows up. It’s a whole different level to be plugged in enough to know when new releases hit theaters vs. just being fed new shows and movies by the recommendation algorithm from the comfort of your couch.

LikeLike

They also need to fix their recommendation algorithm to allow for Masala. They are getting better at it, but I still see random oddities, where they have been tricked by a happy poster or a first 5 minutes of the movie into calling it the wrong thing.

But then, they are getting better at that in general, right? I’m seeing categories like “TV shows with a strong female lead” which are much easier to translate than “sitcom” that can mean something totally different in America versus Korea versus India. They just need to expand movie genres to something like “middle-class romance with family issues” instead of just “romance” and throwing everything in together.

Oh, and my biggest problem, they really need to get better at picking screenshots for Indian films! Have you noticed this? It’s often random side characters featured, to the point that I keep thinking I am looking at the wrong movie until I finally realize “oh yeah, that’s the friend of the hero and the heroine’s sister that for some reason on this image”. Like, Bhool Bulaiya has a picture of one of the many comic relief characters, instead of Akshaye or Amisha or anyone famous. A Flying Jatt has Jacqueline in close up, not Tiger, the hero of the film, or anything at all superhero related.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 1:10 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Yes, the screenshots can be random! I get the feeling they’re running tests, because I get different images sometimes scrolling through the same movies on my watch list.

LikeLike

I also suspect, from the minimal experience I have had with pulling screenshots for publicity materials, that they are looking for clean simple images. And there just aren’t that many clean simple images in Indian films! So you end up with whatever random characters were visible in a two frame with a blank background, whether they are the leads or not.

On Mon, Jul 23, 2018 at 1:25 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Thought this would be relevant here

https://www.quora.com/Why-did-Netflix-have-a-hard-time-in-India/answer/Deepak-Mehta-2

LikeLike

Thank you! I don’t usually like quora, but that was a great answer.

On Wed, Jul 25, 2018 at 11:45 PM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

That’s a shame! Coz Quora is where I found you. But it became such a hostile place, didn’t it?

LikeLike

Yeah, and they don’t seem to care. That is, the quora supervisors. I reported abuse so many times, and they didn’t do that much about it, so I finally decided it didn’t make sense for me to be providing content for a website that didn’t bother to support me at all.

LikeLike