This took an interesting turn! I wanted to talk about Sujata and caste in India, and I ended up spending a lot of time talking about race in America. Because, in the end, they are both about social illusions we have been trained to accept, which can be broken by something as simple as hearing a baby’s cry.

Do you know about the American term “passing”? It means when a child is born to an African-American family but is light-skinned enough that they can “pass” as white. It’s kind of a hidden thing in our culture, from both the white and Black side of things. From the white side, we are scared to acknowledge just how thin the line is between white and black, how imaginary really. And that the line is that thin in America because of generations upon generations of rape by white men of Black women resulting in mixed babies. And from the Black side, there is the guilt of it. That you have given up your heritage, you have crossed to the other side of the line. That moment that a white person treats you as one of “us” and you realize that means you are no longer one of “them”.

(to add another layer to it, “passing” characters in the few films that dealt with it were usually played by “white” actresses)

And then there’s the flip side of it, becoming more and more common now, a child who was born “Black” (whatever that means), but then adopted into a “white” family. They are raised in white culture, as one of “us”. But early on, they learn that the people on the street see them as “other”. How do you deal with this?

Well, the good news is, in America, there are a lot of tools to deal with it now. Interracial adoption was frowned upon for years and years, thinking that children could not “adjust”, that it would be better if they stayed with “their own kind”. And then the pattern shifted sometime in the 70s-80s, suddenly color blind adoption became the thing, so long as there was love it would work out was the thinking. Now there is a kind of medium point. White parents of African-American children, or children of any other race, try to keep them in touch with their culture by birth, read picture books with kids who look like them, tell stories of kids who look like them, bring them to neighborhoods and churches with people who look like them. But it is still an issue, still a constant negotiation between your identity by birth and your identity by family and how those two fit together.

So, why am I talking about all of this? Well, Sujuta is the rare movie that deals with caste in India in the same way race is handled in America. Which is, I think, correct. There’s more to it than that, certainly, the history behind the issues is very very different. But you have to get back to the basic level, to the idea that a pure innocent baby was somehow born “wrong”, and that a family can never be made whole across that line.

What I love about Sujata is that the primary issue is not romantic love that crosses caste boundaries (a much more common tale in Indian film), but family love that crosses caste boundaries. This is, somehow, more dangerous to the status quo. In the same way acknowledging that a white family can love a Black baby and vice versa is dangerous in America.

Loving a child that you raise, or even loving a child that you hold in your arms for a moment, is the most basic level of human nature. It is how we have survived as a species, that natural yearning towards the next generation. You can see it constantly in stories of parents by adoption. One second with their baby, and this is Their Baby forever and ever. Romantic love is a mystery, it happens or it doesn’t happen. Romantic love crossing caste boundaries is magical and rare and impossible to predict. Family love crossing caste boundaries (or race, in America) is as simple as putting a baby in your arms. That’s all it takes.

(This is also why Bajrangi Bhaijaan had such a powerful story. How can even the hardest religious conservative look at that little face and not acknowledge her innocence and humanity?)

But, if we accept that, then it means all of these boundaries we have set as a society are allusions. Race, caste, class, whatever it is in your particular culture, whatever is the impossible “they are not like us” taboo, it can be broken down as easily as a baby’s cry. Everything else is an illusion we have set for ourselves. Sujata, the film, comes alive when it deals with that question, the question of the bond between parent and child and how we try to deny it to ourselves. And how that denial tells us that our beliefs are false. Any belief that denies the possibility of love for a child, well, that is wrong.

SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS

Sujata, the character, never really comes alive. Which is I guess what the director wanted? Nutan is brilliant in the role, of course. But she plays a woman who has always accepted what was given to her, never fought for herself. What is brilliant is that it shows us, in a microcosm, what casteism does to it’s victims. Nutan does not even know she is low caste until late in the film. But those around her know and therefore treat her slightly different. And she grows up stunted and bent because of that treatment. Her clothes are never quite as showy as her sister, her room not as nice, her education not as good. She is less encouraged to speak, less encouraged to meet strangers. Her labor for the household is expected, she is not thanked for it. And she is casually asked to do more, to sacrifice more. Even without sitting down and telling her that she is low cast and therefore should be grateful they tolerate her existence around them, the message is clear.

This was the first way I was reminded of race and passing. It’s not quite the same, you aren’t necessarily passing because your family has raised you that way (although there are cases of it, most often biological children whose mothers manage to pass them off as fully “white”), but as an adult, you have to break through all those internalized aspects of racism. It’s not just about “looking white”, it’s about feeling white, all those lessons you have been taught that you need to unlearn.

Caste isn’t something that is there to be read on someone’s face. But it is there in their attitude, their behaviors, all the things they have been taught to be. You can see it not just in low castes, but in high. I mean, I do the same thing. I work near where my father grew up and my grandfather still lives. I can walk down the street and know that something about the way I am walking, the stores I am going into, the kind of clothes and jewelry I am wearing, tells people exactly who I am and who my family is and where I came from. That’s also, by the way, a big advantage for me when I travel in India. I’m white, so I clearly don’t fit into any of the standard categories there. And the result seems to be erring on the side of assuming I am super super powerful and important and wealthy. Okay, so my rickshaw fees are ridiculous, but I can also walk into any building I want and get a personal guided tour.

(Merle Oberon benefited the other way. In Bombay, she was a lowly mixed race shopgirl. In America, she could “pass” as a white actress with a British accent)

Where was I going with this? Right! That class and caste are something we carry with us based on how we have been trained by how we are treated in our lives. Nutan doesn’t have to know she is low caste. She just has to know that she is somehow “less than” everyone else in her family, that she should be apologetic for her very existence for some unknown reason. That is all “caste” is, after all, the way we are treated by others. A social construct.

What makes this film so fascinating, and so good, is that it explores how it feels to be the ones meting out that treatment. Nutan’s parents love her, love her so much. We see that right from the beginning. A crying baby is brought to their house, and their attitudes and expressions tell us how much they are resisting the instinct to take this child into their arms and love it. So they compromise, make the nanny care for the baby, so they know it is safe and happy and healthy, but their conscious can still be clear.

There is a moment early on, when Sulochana is singing a lullaby to her biological daughter and hears baby Nutan crying in the other room. She moves across the room as she is singing, until she is standing at the opening leading to Nutan’s room. And you can see how hard it is for her to hold herself back from going inside and holding the other child. There is the same love there, but it can’t be acknowledged. It’s a shameful miserable love that grows stronger the more she denies it.

This love is SO MUCH more than the love Nutan finds as an adult with Sunil Dutt. Although, can we take a minute here for how shockingly beautiful Sunil Dutt was? I had only seen him in Mother India and Waqt and his old man roles before this. He came onscreen, and I had this sudden feeling of unique and yet familiar and powerful energy, and realized it was Sanjay! This was like looking at a young Sanjay, all over again. That same kind of crooked power.

Which works well with his role here. Any other young man would come to their house and see Shashikala, Nutan’s adoptive sister, vivacious and pretty, with elaborate hairstyles and fancy modern dresses. But Sunil is just slightly off from the regular young man. And so, naturally, he would seek out the one who is slightly “off” as well, Nutan, hiding herself and hard to know. But this love, Sunil seeing her, really seeing her, and liking her, and Nutan blossoming under his attention, that is nothing compared to the agony of the love of her parents for her and their struggles with it.

The structure of the film is brilliant, in how we rapidly jump from babyhood to adulthood with those ever increasing compromises just implied along the way. When baby Nutan first joins their household, they try to stop themselves from so much as touching her. By the time she is a little girl, they casually touch her, but flinch at sharing food. As a young woman, she cooks for the whole household and serves them their food. The distance is almost invisible now. But, because we saw the beginning, we know that it is still there. We can trace the little moments of hesitation, of resistance, any time they get the urge to touch her head, to pat her cheek. And then stop themselves.

And we also see how none of that hesitation has been carried through to the next generation. This is another part of those unnatural “taboos”. We may not be able to let ourselves break them entirely, but our nature turns away when we think of passing them onto another generation. Nutan’s parents have not, by word or look or action, taught their other daughter that Nutan is any less than her. Shashikala calls her “didi”, hugs her, teases her, fights with her. And joyfully arranges her little romance, sees that Sunil likes her and vice versa and arranges for them to be alone together. The rest of the family may not even be able to conceive of a relationship between Sunil and Nutan, but to Shashikala it is as natural as one between herself and Sunil, or any other young couple.

The constant refrain of the film is that Nutan is “like” their daughter. Shashikala is their daughter, Nutan is the girl they raised who is “like” their daughter. And this hurts Nutan every time it is repeated. Not because it is hard to hear the truth, but because it is hard to hear a lie. Without knowing why they lie.

Nutan is their daughter, in every sense of it. And yet, they will not acknowledge her. Why? What makes their love for her somehow shameful? And her love for them?

Which brings me to the end. A complicated scene. And one which means I have to talk about popular myth and Dr. Charles R. Drew.

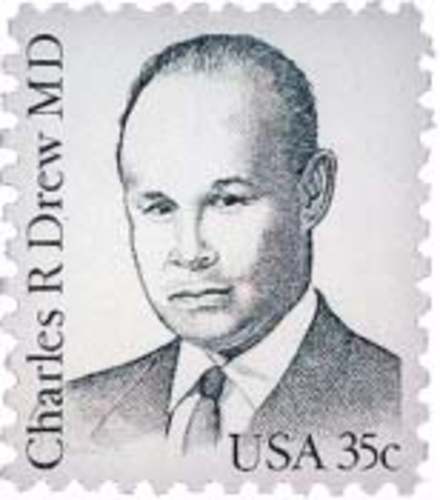

Dr. Charles R. Drew was one of the pioneers of blood transfusions in America, helped save thousands of lives with his discoveries on how to safely store and transport blood. He died in a car accident in 1950. At that point, blood was routinely labeled “Black” and “White” in America. A popular myth sprang up that Dr. Drew had died because he was refused blood at the hospital as there was no “Black” blood available. One of those stories that feels true, but isn’t really. Because it could have been true, on a different night at a different hospital. Black men and women and children died all over America because there was no “Black” blood, no “Black” doctor, no “Black” hospital available to them.

(Our American policies denied his very humanity, and forced him to go to medical school in Canada, but then we gave him a stamp, so that makes up for it, right?)

What is true is that Dr. Drew resigned from his position with the American Red Cross shortly before his death in protest of their practice of segregating blood donations. Because there is no scientific difference between “Black” and “White” blood. But of course you couldn’t admit that in America in the 1950s, because that leads you down the path of admitting there is no real difference at all between “Black” and “White”. The same reason white society didn’t like to think about people “passing”, about mixed race children, about any of it.

I don’t know how deep caste runs in India. I wasn’t raised in it. But I was raised in the racial world of America and I know how deep that runs. And blood transfusions, organ donations, that is the final line for us. Almost as deep as mixed race children. To admit that our bodies are the same in every way, so much so that we can share body parts, that was a line that it was awfully hard to cross.

Sujata combines two hard lines in one. Really, three hard lines. First, there is the idea of Sunil and Nutan marrying, mixing bloodlines. On top of that, this romance means that Sunil has picked one sister over the other, Nutan’s parents see one daughter’s heartbreak in another daughter’s happiness (being unaware that Shashikala herself encouraged the romance and has no interest in Sunil). And finally, during this argument, Sulochana hits her head, requiring a blood transfusion.

Reading the plot description online before seeing the movie, it all seemed remarkably coincidental, the blood transfusion coming after the argument. And the way the argument came up out of nowhere. But they are all the same thing, really. An intercaste marriage, adoptive versus biological daughter’s happiness, and a blood transfusion. It’s all about love. About the battle between heart and head. Or, not head, but prejudice and heart.

Sunil has won out, his heart tells him to marry Nutan and that is what he will do. Soluchana cannot resolve this, her heart is torn between her two daughters, with her head telling her to choose the biological and upper caste one over the other. And the blood transfusion is the final test. Prejudice tells us that it won’t work, that Nutan’s blood cannot mix with her mother’s. Heck, prejudice tells us that Nutan shouldn’t even offer, that she should hold her mother’s actions against her. But love tells her to do it, that this woman is her mother in the end, and she loves her.

That is why, in the end, Tarun Bose (Nutan’s father) announces that she has defeated them. She has proved, through her love for them, that she really is their daughter and therefore they really are her parents. All those games they played with themselves, saying that if they didn’t put her in the same bedroom, or give her the nice clothes, or the good education, it wouldn’t count, they didn’t really love her, those are washed away. The reality that is left is that love is all.

One final thing about the film. This is my second Bimal Roy film (after Bandini, did NOT like it). And I was really struck by how simple he kept it. We spend most of the film moving around the family home. And the entire cast of speaking parts is just a handful of characters. Even the framing of the scenes, the camera is kept tight on faces, or at the most a few bodies in conversation. He is not interested in an epic sweep of events, there is nothing like that fancy montage sequence in Bandini showing us the entire jail. He just wants to look at these people.

(Did not like Bandini, this sequence is still super cool)

Because that’s all social statements are about, people. If you talk about caste as a social evil, that’s hard to grasp, and doesn’t get at the root of the problem. The root of the problem is turning away from our humanity, from our natural instincts. You don’t have to think big and philosophical, you just have to look at the people around you and do what your heart tells you is right.

I just realized, reading your description of the story, that this is the original of a Telugu film released in 1972, titled “Kalam Marindi” (The times have changed). Funny thing is, while that was a widely acclaimed film, I don’t remember anyone mentioning that it was a remake.

I just wanted to mention that, regarding interracial adoptions, it’s always the non-white kids being adopted by white parents, and never the other way around. The same holds true for international interracial adoptions. So can we really point to them as evidence of the breaking down of racial prejudice?

The rise of international surrogate pregnancies raises the issue in a new way, however. There is a Telugu film, titled “Yasoda”, (I think, not 100% sure), which deals with a surrogate pregnancy where the foreign parents refuse to take the baby for some reason after he’s born, so he’s brought up by his Indian “mother’, who is biologically unrelated to him. The point is that the film deals with the prejudices both mother and child have to overcome because he’s white and she’s not. I read about it before its release, and thought it sounded fascinating, but I haven’t been able to locate any copy of it for viewing. So I’m hoping this might ring a bell with some of your readers, and I might get to watch it after all.

LikeLike

I only know American adoption policies, obviously, but there are actually white kids raised by non-white parents. It’s just far far less common. Because of social and economic barriers and so on, but it is still a thing that happens. And, I think, is happening at an ever increasing rate. I wish it would be more common, because I do think mixed families are an important part of breaking down social barriers. Besides it just being good for every child to have a home. But then a white child adopted into a non-white family in American culture would have a different set of concerns than the reverse. Everything they see in popular culture would be directed at them, but not at their parents. So I guess the experience would be closer to the “passing” child, who looks considerably lighter than their biological parents but was still raised in Black culture.

Anyway, I am really interested that this film was remade! Watching this version, it feels very “Bengali” in a way I can’t quite put my finger on, even though it was made in the Hindi industry. Something about how caste is replicated and how reform is discussed felt very Brahmo Samaj-y, rather than Communist/Socialist. I would be curious to see how it changed slightly when made in a different language/ethnic area.

And that surrogacy film sounds fascinating!

On Fri, Jun 30, 2017 at 11:39 AM, dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

This classic post slipped away from my eyes earlier and I noticed it just today. Good review.

Speaking of adoption and surrogacy, there is a Telugu movie made four years ago – ‘Welcome Obama’. It is not a commercial success but okay to watch. But the American woman in this movie (Rachel) is very loud mouthed and that is the only thing I remember.

LikeLike

loud mouthed American seems fairly accurate.

LikeLike

Pingback: Friday Not-So-Classic: Dil Hai Tumhaare, The Puppet! THE PUPPET!!!! WHY?!?!?!?!? | dontcallitbollywood

Thanks for this one. I now have a movie to watch. And Merle Oberon has one of the most fascinating -not to mention pretty sad- stories I’ve heard.

For better or worse, I always look at caste in India through the prism of American race relations. I know its not an exact comparison and I lose a lot of granularity that’s specific to the caste system but I’m more familiar with the race terminology than caste ones. My mind tends to jump on the commonalities between the two.

If you’re interested, there was this really fascinating documentary on caste in Tamil cinema that’s subtitled. I will say it gave me a lot to think about and opened my eyes to caste in a way I never realized existed in movies.

LikeLike

thank you! Caste is so tricky to follow, because there are all those variations region to region and era to era and so on. Not to mention how religion plays into it.

LikeLike

Oh I completely understand! I tried to read up on the reservation system once and tried to find a list of the groups it applies to and quickly gave up. And I was just looking at Tamil Nadu’s lists. I can’t even imagine trying to keep up with all of this across all states and specifics.

LikeLike

Pingback: Film Reviews | dontcallitbollywood

Pingback: Friday Classics: Dabangg!!! The Most Progressive Film You Never Noticed Was Progressive | dontcallitbollywood

Pingback: Netflix List for December! Aamir Signs His Netflix Deal | dontcallitbollywood

Pingback: Starter Kit: Samarth-Mukherjee Edition, Rani, Kajol, Tanisha, Tanuja, Nutan, Shobha | dontcallitbollywood

Because my sudden interest in super old films I finally watched this one and I’m pretty annoyed that the version I ended up watching had 30 minutes chopped off (I kept on hearing discussions about Sujata committing suicide and either I missed it or it wasn’t in the version I was watching?) but even then I thought this film was lovely. It’s interesting how Nutan’s characters both here and Bandini are on the passive side but I feel like her character in Sujata is more clear maybe because we got to see quite a bit of her as a child and in the present we see her trying to come to terms with her place in the family after the caste reveal (birthday party scene really sticks out to me). And Nutan is of course wonderful so you really feel for her.

Like you said, this movie is more centered around familial love than romantic love and I appreciated that a lot. The childhood sequences where you can feel the parents really struggle with their growing affection were done so brilliantly. That being said I did still liked the actual romance we did get. Sunil Dutt has been really hit or miss for me so far but I thought he was absolutely wonderful and charming in here! His expressions when he’s singing to Nutan on the phone get to me every time. With the exception of Bandini, I quite like the way how Bimal Roy portrays romantic relationships for some reason, even in his social message movies, which I guess is kind of strange because with the exception of Madhumati (full blown dramatic swoony gothic romance!), I don’t think people really associate Bimal Roy with romance.

LikeLike

I don’t remember a suicide sequence either, but I might just have a bad memory.

Sunil Dutt is just swoony in this movie, partly because he gets to be perfect, the character growth is all from the parents, Sunil is already the ideal man. Can you imagine a version where he stopped loving her after learning her caste and then had to be taught not to care? BLECH! So much better to just have him be the person all along saying “does this really matter?”

On Wed, Apr 22, 2020 at 1:42 PM dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLike

Yeah! He was somehow both sensitive but also direct and decisive! In most movies I feel like the hero would be shocked and be angry about the caste reveal but in this movie he did not care and was just like “oh you’re going to disinherit me? alright then!” to his family then just walked away and it was great.

LikeLike

Reminds me of Shashi in Kabhi Kabhi finding out that Neetu is adopted “Oh, she’s adopted? How lucky we all are that happened and we get to know this wonderful young woman now! Great news! Moving on, let’s go back to wedding planning”.

On Wed, Apr 22, 2020 at 3:04 PM dontcallitbollywood wrote:

>

LikeLiked by 1 person